Fact file:

Matriculated: 1905

Born: 20 June 1886

Died: 15 April 1918

Regiment: Army Chaplains Department, attached to Royal Garrison Artillery

Grave/Memorial: Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery: XXVI.FF.9.

Family background

b. 20 June 1886 as the third son (fifth of six children) of Sinclair Frankland Hood, JP (1851–97) and Grace Eleanor Hood (née Swan) (1859–1943) (m. 1876). At the time of the 1891 Census, the family (plus five servants and a German governess) was living at Nettleham Hall, four miles north-east of Lincoln (ravaged by fire in 1937 and now a dangerous ruin); they later lived at 24 Cumberland Mansions, George Street, Marylebone, London W1.

Parents and antecedents

The Hood family was originally Scottish, but an ancestor, John Hood, came south with the Royalist General Monck (1608–70) who was on his way to London to restore Charles II to the throne, and the family settled in Nettleham Hall in 1828. Hood’s father, who studied at Magdalen from 1871 to 1875, was a landowner, and Hood’s paternal grandfather, William Frankland Hood (1825–64), was a landowner as well as an ordained clergyman, who, until forced to live abroad for health reasons, was the Perpetual Curate of Helmswell, Lincolnshire.

Hood’s mother was one of the three daughters (five children) of the Reverend Charles Trollope Swan (c.1826–1904) and Grace Swan (née Martin) (1824–95) (m. 1853). Charles Trollope Swan was a very wealthy landowner who, despite being a clergyman, left £295,000 (c.£23 million in 2005). After studying at Christ’s College, Cambridge (LLB 1st class 1849), he was ordained deacon and priest in 1850 and spent all but two years of his professional life in parishes in the Diocese of Lincoln: he was Vicar of Dunholme, 1850–57; Rector of Brettenham, Suffolk, 1857–59; Rector of Welton-le-Wold, 1859–78; and Rector of Sausthorpe, 1878–80. When he took up the final living, he succeeded his father, the Reverend Francis A. Swan (c.1787–1878; BA, 1808; MA, 1810; BD, 1818), who had been a Demy of Magdalen College, Oxford, from 1807 to 1810, a Probationary Fellow there from 1810 to 1824, and the Lord of the Manor and Rector (and Patron) of Sausthorpe from 1819 to 1878. Grace Martin was the only daughter of the Reverend Samuel Martin (1791–1828) and Frances Eleanor Williams (1793–1849) (m. 1823), and Samuel Martin was the Vicar of Coleby, Lincolnshire, from 1823 to 1828.

Nettleham Hall, Lincolnshire, after the fire of 1937; it is now a dangerous ruin in overgrown woodland.

Two ladies and a boy with a coachman (possibly the irascible Mr Gibbons, who, when aroused, would vent his wrath on small boys by lifting them up by the ears) in an open carriage pulled by two horses

(from Christobel Hood’s manuscript biography of her husband)

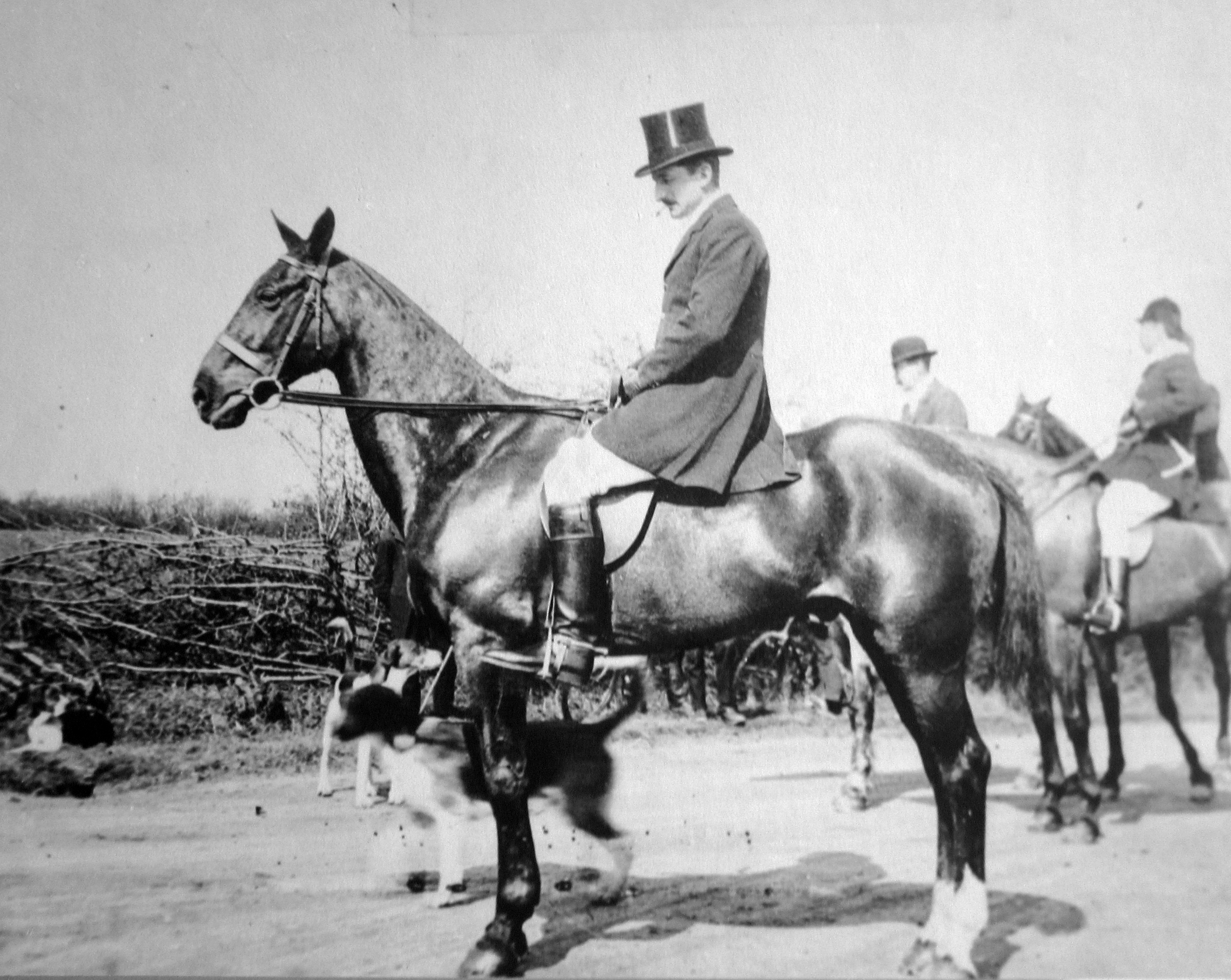

In several respects the Hoods were typical of the English gentry, and according to the biography of Ivo that was written just after World War One by his widow, Christobel Hood (see below), and that now exists as a manuscript (see the Bibliography), “hunting in winter and village cricket in summer were two of the chief interests of life at Nettleham”. But she also says that although both Eleanor and Sinclair Frankland were “notable followers of the Burton Hounds”, the Church was the centre of their family life and that they had paid for the restoration of Nettleham Church soon after their marriage in 1876: “it was their delight to beautify [the church] in every way”. Whereas Grace Eleanor’s “most valuable contribution [was] her wonderful organ-playing”, Sinclair Frankland read the lessons and “helped in every possible way on weekdays as well as on Sundays”, adding that “his horse could often be seen waiting outside the Church whilst he attended the daily Service before going hunting”. The Hood children also loved the Church and its services, “especially when it was the Sunday for the Sung Celebration” which they called a “nice Sunday”, probably because the service included the Nicene Creed that had been formulated by the First Council of Nicea in AD 325 and was much longer than the earlier Apostles Creed. During the summer holidays, the Hood children often went to Skegness, on the Lincolnshire coast, where their maternal grandfather had bought the family a seaside house.

This uncaptioned photo of a man on horseback in hunting gear is included in Christobel’s manuscript biography and may possibly depict Sinclair Frankland Hood.

Sinclair Frankland also added a large galleried hall to Nettleham Hall, where he displayed the huge collection of Egyptian antiquities that had been assembled by his father and continued to attract such eminent visitors as the Egyptologist William Flinders Petrie (1853–1942) until the Hall burnt down under mysterious circumstances in 1937. The hall also had an organ half-way up the stairs, and a grand piano below – and it was here that the children learnt at an early age both to enjoy and to make good music. Christobel describes the Hall as “big enough for the largest family to find room for itself on wet days, whilst outside, the garden and park and farm were happy hunting grounds”, adding that in the spring, “each child was given a lamb out of the flock and they were allowed to have the proceeds if it was sold later”.

Christobel describes Sinclair Frankland’s death in May 1897 at the relatively young age of 46 as “a terrible break in [Ivo’s] family life”. But like other relatively well-to-do English families, the Hood family had already, for the sake of Grace Eleanor’s health, begun to spend the winter months of each year in San Remo, on the Italian Riviera, just across the border with France, in order, as Georgina Ferry put it in her admirable biography of Dorothy Hodgkin, to “escape the chill of draughty country houses”. But the family’s inheritance on Sinclair Frankland’s death – £8,564 14s. 11d. (the equivalent of £669,525 in 2017) – enabled them to escape the discomfort and expense of living in small Italian seaside hotels by having a house built near San Remo which Christobel described as “standing very beautifully with a view of the sea on the south, and of Monte Caggio [3,576 ft high] on the west” and which they named the Villa Lincolnia.

Alban Hood, Ivo Hood, Grace Eleanor Hood (their mother), Grace Mary (“Molly”) Hood and Dorothy (“Dolly”) Hood outside the Villa Lincolnia, the Hoods’ villa in San Remo

(from Christobel Hood’s manuscript biography of her husband).

Probably a photo of the Villa Lincolnia

(from Christobel Hood’s manuscript biography of her husband).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Grace Mary (“Molly”) (1878–1957), later Crowfoot after her marriage in 1909 to John Winter Crowfoot (later DLitt, CBE) (1873–1959); four daughters;

(2) Dorothy (“Dolly”) Agnes Hood (1879–1965);

(3) Edward Thesiger Frankland (later Lieutenant-Colonel, DSO, Croix de Guerre) (1880–1918); killed in action 15 May 1918 when serving as the Commanding Officer of 38th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery); married (1906) Marjorie Blanche Dalglish (1886–1965), one son, one daughter; they had become estranged by c.1917. Her later name was Poston after her marriage in 1918 to Lieutenant-Colonel William John Lloyd Poston, DSO, RFA (c.1881–1950); two children;

(4) Alban John Frankland (1881–1927); died on 19 January 1927 of the long-term effects of wounds received in action on 5/6 May 1915 at Hill 60;

(5) Martin Arthur Frankland (“Chuff”) (1887–1919); married (1915) Frances Ellis Winants (b. c.1890 in the USA, d. 1960 in Bayonne, NJ, USA); one son.

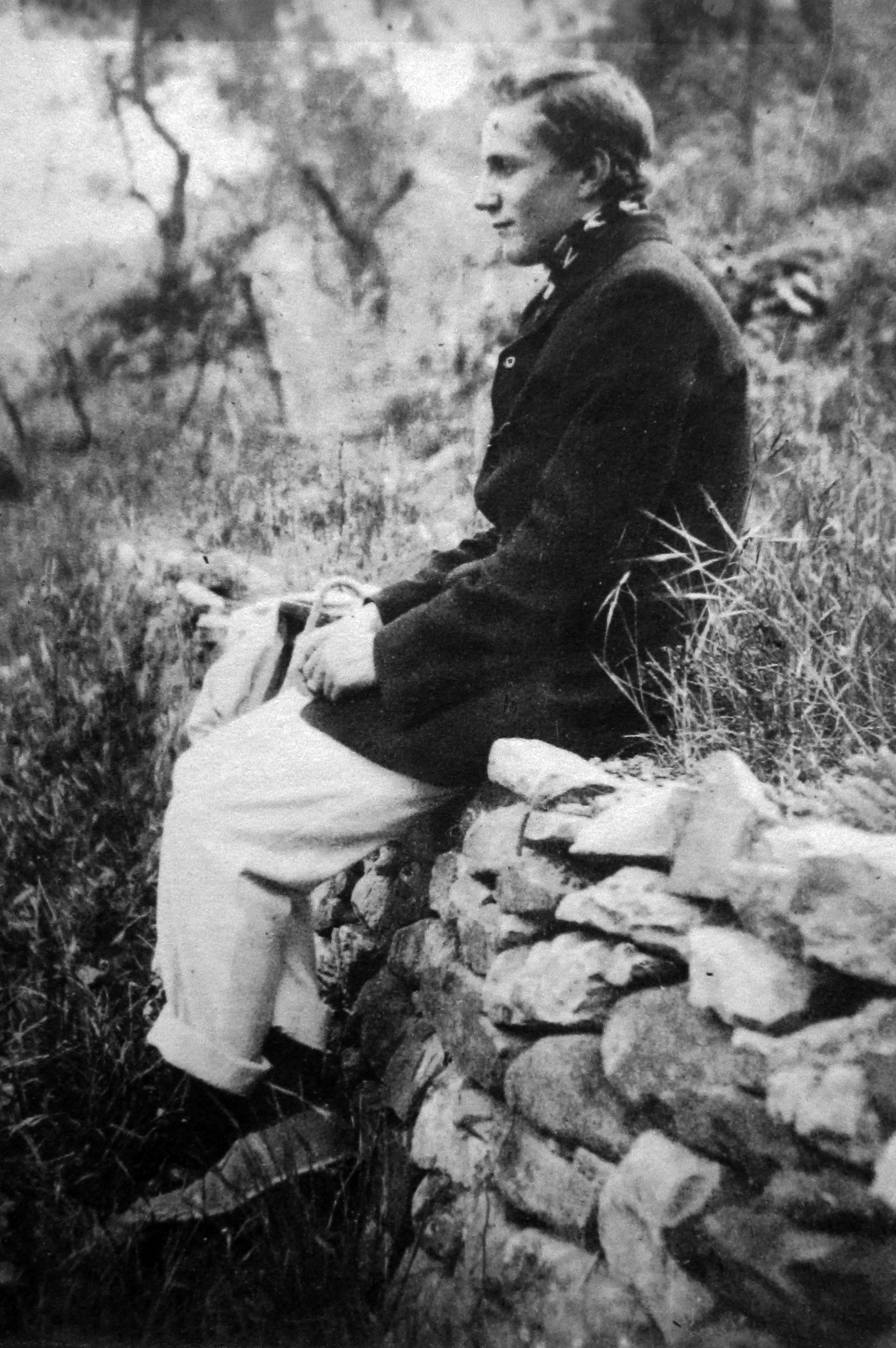

Grace Mary, who was known to her family and friends as Molly, was, in common with the rest of family, interested in music and the Church, and after being educated at home, she attended finishing school in Paris for a year. But although she was then invited to read for a degree at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, by Dame Elizabeth Wordsworth (1840–1932), the College’s founding Principal (1879–1909) and the daughter of Christopher Wordsworth (1807–85; Bishop of Lincoln 1869–85), her mother discouraged her from doing so, probably because she did not want to be deprived of a companion. Nevertheless, Molly was fascinated by botany and archaeology, and while at San Remo she took part in botanical/archaeological expeditions in the nearby Ligurian Alps, where, in 1906, she first visited the remote Neolithic cave dwelling at Tana Bertrand, near Badalucco. In 1908–09 she returned there to excavate the cave and discovered 300 beads, on which she eventually published a paper in 1926.

Grace Mary [“Molly”] Crowfoot (née Hood).

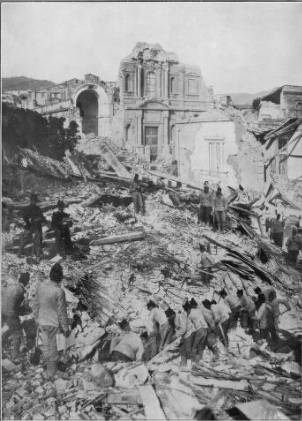

The ruins caused by the Messina earthquake (from F. Matania, ‘Searching the ruins. Messina Earthquake (28.xii.1908)’, The Sphere, 36, no. 469, 16 January 1909, p. 6).

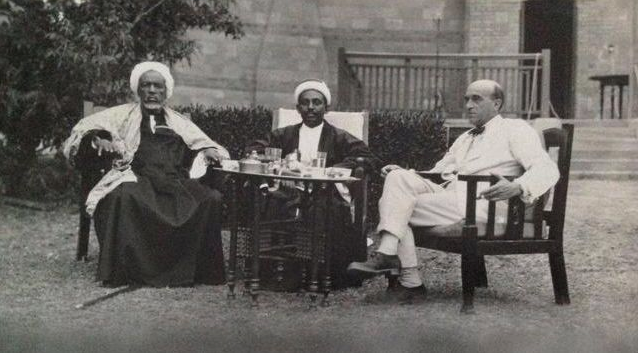

In 1909 Molly married John Winter Crowfoot, the son of the Chancellor of Lincoln Cathedral, who was currently Assistant Director of Education in the Sudan, and the couple spent the five next years in Cairo, where Molly gave birth to three daughters, pursued her already developed botanical interests, learned Arabic and photography, involved herself in local welfare projects (such as the children’s dispensary at Fayyum), and produced a book entitled Some Desert Flowers, which she published in Cairo in 1914. When war broke out, the family returned to England for a year, but Molly and her husband went back to Cairo in 1915, where she helped to nurse the wounded from Gallipoli.

In 1916, Molly and John moved to the Sudan, where she learned to use the Sudanese ground-loom, honed her already considerable expertise in spinning and weaving, and began to study the depictions of spinning and weaving that had been found in Pharaonic tombs. During her time in the Sudan she also initiated government sponsored maternity services, helped set up the Midwifery Training Centre in Omduran, and introduced Mabel Wolff (1890–1981) to train Sudanese midwives there. After the birth of a fourth daughter in 1918, Molly returned to England, and from 1920 onwards she and her husband leased the Old House, a large Georgian mansion, in Geldeston, a village on the Norfolk/Suffolk border near Beccles, where John Crowfoot’s family had practised medicine for five generations and where John himself had been at school. In 1932 she and the French (Alsatian) ethnologist Louise Baldensperger (1862–1938) published From Cedar to Hyssop, an early work of ethno-botany. Until 1937, by which time their four daughters had left home, Molly and John spent winters in the Middle East and came back to East Anglia for long summer visits. In Geldeston, Molly and her sister Dorothy Agnes became committed members of the League of Nations Union, and she was also an active member of the Labour Party, the Parochial Church Council, and the Village Produce Association.

Her interest in looms, tablet weaving and textiles continued to develop both throughout her time in England and after her return to the Sudan in 1923, and she began to publish essays in learned journals in which she used her growing expertise to shed light on archaeological discoveries. In 1928 she published Flowering Plants of the Northern and Central Sudan and in 1933 she followed this with Some Palestine Flowers. When, in spring 1927, John became Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and was put in charge of several excavations, Molly worked with him in the field, organized the excavation headquarters, oversaw the publication of the resultant reports, and wrote several more papers of her own. In 1938 the couple came back permanently to Geldeston, enabling Molly to work on the Anglo-Saxon ship-burial site at Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge; to publish a joint paper on the embroidered panels of Tutankhamun’s tomb; and to write a paper on the linen wrappers of the Dead Sea Scrolls after they were initially discovered in a cave at Qumran on the northern shore of the Dead Sea between November 1946 and February 1947. During the last 20 years of her life she was used increasingly as a specialist consultant and lecturer, and in 1951 she gave the Munro Lectures on primitive weaving at the University of Edinburgh. In 1957, Molly, together with her husband and Kathleen Kenyon (later Dame), published The Objects from Samaria (Samaria-Seebaste III), whose appearance had been greatly delayed by World War Two. By the time of her death she had written or helped to write over 60 publications, and had made a significant contribution to the training of the next generation of textile archaeologists in Britain and elsewhere.

John Winter Crowfoot, CBE, was the son of a clergyman and educated at Marlborough College and Brasenose College, Oxford. In 1897 he travelled in Greece and Asia Minor as a student at the British School of Archaeology in Athens and from 1897 to 1899 he studied Archaeology at the University of Heidelberg. In 1901, after spending a year (1899–1900) as Lecturer in Classics at the University of Birmingham, he went to Egypt as a teacher and civil servant. In 1903 he was appointed Deputy Principal of Gordon College, Khartoum (now the University of Khartoum), and from 1914 to 1926, when he retired from the Sudan Civil Service, he was the Sudan Government’s Director of Education and the Principal of Gordon College. He then became Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, where he excavated the Hill of Ophel, Jerusalem (1927–29), and the earliest monuments of Byzantine Christianity at Jerash (1928–30), Bosra (southern Syria), and Sebastiya (Samaria) (1931–35). In 1935 he retired from his post in Jerusalem and he finally returned to England in 1938. He published most of his discoveries in a series of volumes that appeared between 1927 and 1957, but summarized some of the material in his lecture on ‘Early Churches in Palestine’, which he gave to the British Academy in 1937. From 1941 to 1945 he was Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries, and from 1945 to 1950 he chaired the Palestine Exploration Fund.

Molly Crowfoot (seated) and her four daughters (from left to right): Joan (seated with the doll), Dorothy (standing with the doll), Diana (the baby) and Elizabeth; the lady standing at the rear is Katy, the children’s nurse

An account of Molly and John’s four daughters is given in a separate section below.

Dorothy Agnes, or Dolly as she was known, was, like her older sister Molly, educated at home and subsequently spent a year at a finishing school in Paris, after which she was her mother’s constant companion during the winters that she spent near San Remo (see above). It was here, in 1907, that she conducted an amateur performance of Dvořák’s Stabat Mater (1876–77), and here, too, that she gradually became a close friend of Christobel Hoare, Ivo’s future wife (see below). While on holiday in San Remo at Christmas 1908, she and her sister Molly travelled down to Sicily to help in the aftermath of the Messina earthquake of 28 December which claimed c. 60,000 victims, among whom were the Revd Charles Boulsfield Huleatt together with his second wife and four young children (see above).

Even before her brother Edward Thesiger Frankland was killed in action (see below), Dorothy Agnes helped to look after his two children following his separation from his wife, probably in 1917. During World War One she was a volunteer nurse and she played a significant part in the upbringing of her four nieces during their parents’ absence after the war. She also nursed her younger brother Alban John Frankland during his final illness (see below), and he returned her kindness by leaving her his entire estate of £55,153 2s. 7d. (the equivalent of £2,265,343 in 2017) – with which she was able to finance her oldest niece’s study of Chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford. She also became responsible for her parents when they finally returned to England in 1938. After World War Two she became a devoted member of the congregation of the Church of St Alban the Martyr, Holborn, a leading representative of the Anglo-Catholic tradition with a high reputation for the quality of its music. She never married and spent her last months in the family home in Geldeston, being looked after by her niece Joan (see below).

Edward Thesiger Frankland was considered to be the sportsman of the Hood family “par excellence” and was described by Christobel Hood as a “capital horseman” and an enthusiastic and well-known huntsman and beagler. After being educated at Bradfield College, Berkshire, he attended the Royal Military College (Woolwich) before being commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Royal Horse Artillery (RHA). He served in the Second Boer War, but then retired from the Regular Army and took a commission in the Lincolnshire Yeomanry. Even before the outbreak of World War One, he had also held a commission in the Army’s Remount Department, where his knowledge and experience as a sportsman were particularly useful. In August 1914, he was given command of a battery in the RHA, and after a few months training, mainly on Salisbury Plain, he went out to France in 1915, where he served at Loos and on the Somme. He was awarded the DSO (London Gazette, no. 30,111, 1 June 1917, p. 5,471), and was mentioned in dispatches several times. In 1917 he was promoted Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel (Brevet Major) and given command of 38th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. The Brigade fought at Passchendaele, and in early 1918 Edward was awarded the Croix de Guerre (Silver Star) for the part that his battery had played in defeating an enemy attack, for which the guns of his Brigade received the same decoration (The Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,360, 2 December 1918, p. 4,348). But in May 1918 he was hit by a shell and died on 15 May 1918 of his wounds in a Casualty Clearing Station, aged 38. Buried: Ebblinghem Military Cemetery, Grave II.B.19 (with the inscription from his Brigade: “In Memory of a Great Colonel”).

On 11 June 1918, his widow Marjorie Blanche, from whom he was estranged, married Lieutenant-Colonel William John Lloyd Poston, DSO, RFA (London Gazette, no. 29,438, 11 January 1916, p. 574), by special licence. They had two children, and their son, Major John Poston (1919–45), MC and Bar (LG: no. 35,492, 17 March 1942, p. 1,261; no. 36,850, 19 December 1944, p. 5,854), an officer in the 11th Hussars since 1940, was killed in action, aged 25, on 21 April 1945 in an ambush while he was returning to the tactical HQ of Field-Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery (1887–1976), on the Luneburg Heath, where he was serving as an aide-de-campe. He is buried in Becklingen War Cemetery, Luneburg Heath, Germany, Grave 15.C.6 (with the inscription: “In loving memory of a gallant officer, loyal friend, devoted son and brother”).

Alban John Frankland died in 1927 of the long-term effects of his wartime injuries, especially his gassing at Hill 60, that had undermined his health. See his separate entry: Alban John Frankland Hood.

Martin Arthur Frankland first went away to a school in Derbyshire, but being musical, like the rest of the family, he later attended Llandaff Cathedral Choir School (founded in 1880 by Charles John Vaughn (1816–97), Dean of Landaff 1879–97), where he, like Alban and Ivo, held a music scholarship. On 29 February 1907 he entered the Royal Navy as a Midshipman; he was commissioned Sub-Lieutenant on 30 April 1907 and promoted Lieutenant on 31 December 1909. He then saw service in a variety of postings, on land and at sea, until, in summer 1915, he was given command of HMS Bluebell, a fast Flower Class fleet minesweeping sloop that had been launched on 24 July 1915, weighed 1,200 tons, and had a complement of 77 officers and men (scrapped 1930). Although Martin managed to ground his ship, on 10 December 1915 a Court of Inquiry allowed him to retain his command but cautioned him to exercise more care in the future. HMS Bluebell was subsequently based in Ireland, where it was involved in the capture of the Irish revolutionary and poet (Sir) Roger Casement (1864–1916), who, in the small hours of 21 April 1916 (Good Friday), was, together with two companions, landed in a small collapsible boat from the German submarine UB22 on Banna Strand, Tralee Bay, County Kerry. The UB22 should have rendezvoused in the late afternoon of the previous day with a German freighter, SMS Libau, that was heavily disguised as the Norwegian Aud-Norge and was carrying arms, including machine-guns and artillery, for the Irish rebels, and Casement and his companions should have been transferred to the Libau in preparation for their arrival in a remote port on the west coast of Ireland. But the rendezvous did not take place and in the small hours of 21 April 1916 the Libau anchored near the rendezvous point before trying to escape into the Atlantic at 13.00 hours on the same day. British Naval Intelligence had, however, heard about the shipment and made preparations, and at 16.30 hours on the same day, the Bluebell, together with her sister ship HMS Zinnia, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander G.F.W. Wilson, RN (1886–1972), was ordered to intercept the Libau. The two British ships began to sail towards the German ship from different directions, sighted her at 17.40 hours, ordered her to stop at 18.15 hours, and started to escort her to the naval base at Queenstown (now Cobh, County Cork) after the Bluebell had fired a warning shot across her bows. But at 09.25 hours on 22 April, just before the Libau entered Queenstown harbour, her Captain, Leutnant der Reserve Karl Spindler (1887–1951), scuttled her using some of the explosives that he was carrying for the Irish rebels.

HMS Bluebell (1915-30).

Meanwhile, before being arrested by the Royal Irish Constabulary and taken to London – where he was tried for treason, found guilty, and executed – Casement had sent messages to Dublin via one of his two companions urging the rebel leaders not to start the uprising, and this, plus the loss of the Libau’s consignment, caused the Easter Rising to be postponed from Easter Sunday to Easter Monday, 24 April 1916.

On 21 April 1917 Martin, whom a witness described as shy and retiring and looking younger than his years, was mentioned in dispatches for his part in the action. By late May 1917, he and his American wife Frances (m. 1915) were living just below his mother’s flat in Cumberland Mansions (see above), but on 17 September 1917 he was placed on the retired list as unfit for duty, having been diagnosed with a terminal illness. On 31 December 1917 he was promoted Lieutenant-Commander, and on 14 May 1919 he died at Chiswick House, Brentford, Middlesex. His son, (Martin) Sinclair Frankland Hood (b. 1917 in Cork), read History at Magdalen from 1935 to 1939 and became an eminent archaeologist who was a Conscientious Objector during World War Two. He began working in Greece in 1948 and specialized in the excavation of Minoan sites, following Sir Arthur Evans (1851–1941) at Knossos, on Crete. From 1952 to 1955 he excavated sites on Chios, in the Eastern Mediterranean, and from 1954 to 1962 he was the Director of the British School of Archaeology in Athens. He published 14 scholarly books, mainly on Minoan sites, and was made an FBA in 1983. His son also studied at Magdalen.

Martin Arthur and his wife Frances are buried together with his parents and Alban in three adjacent graves in the north-west part of All Saints churchyard, Nettleham, Lincolnshire. Martin’s headstone bears the inscription: “He saved many ships and very many lives. Laus Deo”.

Molly and John’s four daughters

The four girls (Ivo Hood’s nieces) were:

(i) Dorothy (“Dossie”) Mary (later DBE, OM and Nobel Laureate) (1910–94); later Crowfoot Hodgkin after her marriage in 1937 to Thomas Lionel Hodgkin (1910–82); two sons, one daughter;

(ii) Joan (1912–2002); later Payne after her marriage in 1937 to Denis Payne (b. 1914, probably d. abroad after 1964 and before 1985); five children;

(iii) Elizabeth (“Betty”) Grace (1914–2005); one son;

(iv) Diana (“Dilly”) Mary Rustat (1918–2018, aged 100); later Rowley after her marriage in 1944 to Graham Westbrook Rowley (later MBE, CM) (1912–2003); three daughters.

Dorothy Hodgkin, by Godfrey Argent, 14 November 1969

(© National Portrait Gallery, London: NPGx18125)

(i) Dorothy (“Dossie”) Mary was born near Cairo in 1910 and, like Joan and Elizabeth Grace, spent the war with grandparents in Worthing, Sussex. During the 1920s, while their parents were in the Middle East, the four girls were brought up and educated by friends and relations near Beccles. Dorothy developed an early interest in chemistry, especially mineralogy and crystallography, attended the Sir John Leman Secondary School in Beccles, and in 1928, not without considerable technical difficulties because of Oxford’s antiquated entrance requirements, she was accepted to read Chemistry, a four-year course, at Somerville College, Oxford, whose Principal from 1926 to 1930, Margery Fry (1874–1958) – the penal reformer, pacifist and scion of the well-known Quaker family and one of the first women to become an English JP – was a family friend. In summer 1928 Dorothy spent the three months between leaving school and matriculating at Oxford helping her parents on their dig at Jerash. Although, at the time, the structure of crystals could not be studied until the fourth year of the Oxford Chemistry course, and then only as a branch of mineralogy, Dorothy pursued her own interest in the subject during her first three years as an undergraduate. Then, during her final year, as her research project for Part II of the Chemistry degree, she was able to carry out research by means of x-rays into the three-dimensional structure of a group of chemical compounds under the supervision of Herbert Marcus Powell (later Professor, FRS) (1906–91). At the time, Powell was the University Demonstrator in Oxford’s Department of Mineralogy and doing pioneering work in the field of x-ray crystallography; he subsequently became Head of the University’s Chemical Crystallography Laboratory.

After graduating in 1932 with a 1st in Chemistry, the third woman ever to do so at Oxford, Dorothy became a PhD student in the highly unconventional and innovative Cambridge laboratory of John Desmond Bernal (later Professor, FRS) (1901–71). Bernal was not only a member of the Communist Party, he was also Cambridge’s first Lecturer in Structural Crystallography, and, like Powell, pioneering the use of x-rays to study biological molecules such as proteins, thereby breaking down the barriers between chemistry and biology. In September 1934 Dorothy returned to Oxford as a Fellow of Somerville, where she began her research into the structure of insulin using x-rays. She obtained her doctorate – on the chemistry and crystallography of c.50 sterol compounds – in summer 1936, and met Thomas Lionel Hodgkin (1910–82) in spring 1937; they married later that year.

Over the next few years Dorothy’s reputation as an expert on the crystalline structure of proteins grew and from early 1941 to 1964 she was in receipt of a large annual grant from the Rockefeller Fund that enabled her to continue that research throughout the war. At about the same time she began to collaborate with Howard Florey (later Sir) (1898–1968) and Ernst Boris Chain (later Sir) (1906–79) in their research into the structure of penicillin. Although the latter problem was solved by summer 1945, the year in which the two men, together with Sir Alexander Fleming (1881–1955), received the Nobel Prize for Medicine, Dorothy’s account of her contribution to their work was not published until 1949, as part of Hans Clarke’s The Chemistry of Penicillin. In 1946, Dorothy became a University Demonstrator in Chemical Crystallography at Oxford – her first University appointment, and a lowly one at that; in 1947 she was made a Fellow of the Royal Society; and between 1948 and 1955 she and her colleagues used their research techniques to arrive at the structure of vitamin B12, a substance that plays a crucial part in the prevention and treatment of pernicious anaemia. As a result, Dorothy’s pre-eminence grew rapidly: she was made Reader in X-Ray Crystallography in 1955; the Royal Society awarded her its Royal Medal in 1956, making her the first woman to be honoured in this way; and from 1960 to 1977 she was the Royal Society’s second Wolfson Professor, a distinction that provided her with a salary of £3,000 p.a. and £5,000 p.a. for research expenses, and allowed her to research whatever she wanted wherever she wanted. In October 1964 she became the third woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, and in 1965 she became the second woman to be admitted to the Order of Merit. But her greatest scientific breakthrough came about in summer 1969, when she and her research team finally cracked the structure of insulin. In 1976 she became the first woman to be honoured with the Royal Society’s Copley Medal since its institution in 1731, and from 1977 to 1978 she was elected President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Throughout her adult life Dorothy was a committed humanitarian socialist and associated herself with such related causes as nuclear disarmament, opposition to the Vietnam War – which included her becoming a member of a commission that investigated alleged US war crimes and environmental destruction in Vietnam (1970–71) – equal treatment and opportunities for women scientists in British universities, the expansion of British higher education, and the creation of better relations with socialist and communist countries, especially China, which she had first visited in 1959 and where research into the structure of insulin was all but paralysed by the Cultural Revolution of 1966. She became the Vice-President of the Medical and Scientific Aid Committee for Vietnam, Laos and Kampuchea in 1965 and its President in 1971, when she visited North Vietnam as a guest of the government, and during her presidency of the International Union of Crystallography from 1972 to 1975 she worked hard and effectively to have Chinese representatives re-admitted. In 1962 she began to attend the quinquennial Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, which had been initiated by Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein in July 1955 and whose primary purpose was to bring scientists together from the East and the West in order to discuss nuclear disarmament. She presided over the conferences from 1975 to 1988 and in this capacity travelled widely on the organization’s behalf. But after she retired from full-time university work in 1977, the arthritis from which she had suffered since 1938 worsened, making walking increasingly difficult and gradually forcing her to withdraw from her many public interests and commitments. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union awarded her the Mikhail Lomonosov Gold Medal in 1982 and the Lenin Peace Prize in 1987; Bulgaria awarded her the Dimitrov Peace Prize in 1984; and in September 1993, not long before her death, she insisted on attending the International Union of Crystallography conference in Beijing. She is buried in the churchyard at Ilmington, Warwickshire, the village where she and her husband had lived since 1966.

Thomas Lionel Hodgkin was the elder son of the Historian Robert Howard Hodgkin, FRS (1877–1951; Fellow of Queen’s College, Oxford 1904–46 and its Provost 1937–46). He attended Winchester College and then read Classics (2nd in Moderations,1929; 1st in Greats, 1932) at Balliol College, Oxford, where his maternal grandfather, the historian Arthur Lionel Smith (1850–1924) had been a Fellow (1882–1924) and then a distinguished Master (1916–24). In early 1933, Thomas obtained a Senior Demyship – a postgraduate research grant – from Magdalen College, Oxford, and this allowed him, for six months or so, to take part in the major archaeological dig that was being conducted at Jericho by Professor John Garstang (1876–1956). From 1934 to 1936 Thomas was personal assistant to Sir Arthur Grenfell Wauchope, GCB, GCMG, CIE, DSO (1874–1947), the British High Commissioner of Palestine from 1931 to 1938, and became, as a result of this appointment, increasingly critical of all forms of imperialism. Because of the Arab uprising in Palestine of April 1936 and its suppression, Thomas resigned his diplomatic post in May 1936; he had wanted to stay on in Palestine, but was expelled by the British authorities because of his pro-Arab and anti-Zionist sympathies. By the time he met Dorothy Crowfoot in early 1937, he had become a convinced Marxist and joined the Communist Party, and he was also training to become an elementary school teacher, but without much success. Then, after a period when he was “sunk into gloom and inactivity”, he developed an interest in adult education and in March 1937 he began to work for the Friends Service Council, teaching history to unemployed miners in Cumberland.

Thomas and Dorothy married in December 1937 and for the next eight years, with a wife and growing family in Oxford and a flat in Bradmore Road, North Oxford, he spent the week elsewhere, first in Cumberland and then working for the Workers’ Educational Association in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire. In 1945 he was appointed Secretary to Oxford University’s Delegacy for Extra-Mural Studies and in this capacity he made extensive trips in the late 1940s to the Gold Coast, Nigeria and the Sudan, three countries that were working their way towards independence, in order to advise on adult education programmes. Despite being made a Professorial Fellow of Balliol in 1952, he resigned his Oxford post in May of that year, after which he travelled extensively in Africa and held part-time appointments at Northwestern University, Illinois, and McGill University, Montreal. On the basis of his experience in the emerging countries of Africa, he wrote Nationalism in Colonial Africa (1956) and African Political Parties (1961), and in 1960 he edited Nigerian Perspectives (2nd, revised, edition 1975). From 1957 until 1966, he and his family shared 94 Woodstock Road, Oxford, with Dorothy’s sister Joan and her five children. In 1961 Kwame Nkrumah (1909–72), the first Prime Minister of newly independent Ghana (1957), whom Thomas had first met in 1948, invited him personally to become Director of the Institute for African Studies at the University of Ghana in Accra, Ghana’s capital city. Thomas held this post for five years, until Nkrumah fell from power in February 1966, and he then returned to England, where he and Dorothy moved to “Crab Mill”, a house in Ilmington, which his parents had acquired in 1936. After his return, Thomas was appointed Lecturer in the Government of New States at the University of Oxford (October 1965–70); he also wrote regularly for such weeklies as the Spectator, the TLS, and the New Statesman, and he travelled extensively to other countries, often in the company of Dorothy. In 1974, he spent three months in Vietnam, and used this experience to publish Vietnam: The Revolutionary Path (1981), a comprehensive history of the country and its culture. He died suddenly in Tolon, on the Peloponnese, Greece, in March 1982, leaving £246,850 (the equivalent of £967,730 in 2020). His Times obituarist described him as the person “who did more than anyone to establish the serious study of African history in this country”, being particularly keen “to demolish the myth that Africa was a continent without history”.

(ii) Molly and John’s second daughter, Joan, was born near Cairo in 1912, and, like Dorothy and Elizabeth Grace, she spent the war years with grandparents in Worthing. She, too, attended the Sir John Leman Secondary School in Beccles and in late 1923 she and Dorothy were allowed to visit their parents while they were working in the Sudan. In 1929, Joan started to read Medicine at the London School of Medicine for Women but had to withdraw from the course for health reasons. Her developed interest in archaeology, especially flints, led her to register at Cambridge on the Diploma Course in Archaeology, probably in the early 1930s. Although she attended lectures, she withdrew from the course and joined her father, who had been Director of the British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem since 1926, as a working colleague. By the late 1930s she had become an international authority on Near Eastern flintwork, and her book A Hoard of Flint Knives from the Negev was finally published in 1978. After her marriage in 1937 to Denis Payne, who worked as a bookseller and publisher (Managing Director) in Cambridge, she spent two decades raising a family. After her marriage broke up in c.1957, Joan and her sister Dorothy moved into 94 Woodstock Road, north Oxford, an arrangement that lasted until 1966. Starting on 15 September 1958, Joan was appointed a full-time cataloguer in the Department of Antiquities of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, where she worked largely on its Egyptian collection. She completely reorganized its documentation, creating a card catalogue that was highly regarded internationally, since it added considerably to the collection’s scholarly status and usefulness, and in 1993 it was published by the Clarendon Press at Oxford as the Catalogue of the Predynastic Egyptian Collection in the Ashmolean Museum (reprinted 2000). On 8 February 1979, in anticipation of her retirement, the Museum’s Visitors resolved to apply to Council for the award of an honorary MA on the basis of “her outstanding services to the Museum and her international reputation as a scholar, maintained over many years and still in the course of enhancement”. The proposal was duly agreed by Council and approved by Congregation on 19 June 1979, and Joan received the degree on 26 January 1980.

(iii) Elizabeth Grace was born near Cairo in 1914 and, like Dorothy and Joan, spent the war years with grandparents in Worthing, Sussex. She, too, attended the Sir John Leman Secondary School in Beccles, and from an early age was interested in literature, acting and the theatre. For a while she attended the Farmhouse School, near Wendover, Buckinghamshire, an experimental school that had been founded in 1906 by the educationalist and social activist Isabel Fry (1869–1958). A member of the influential Quaker family, Isabel was the sister of the painter and art critic Roger Fry (1866–1934), a member of the Bloomsbury Group, and an influential proponent of Post-Impressionism, and the sister of Margery Fry (see above). From October 1930 to July 1932 Elizabeth Grace studied at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London, and although, at the end of her first year, when she was on the Teacher course, she was awarded a 1st with Distinction, she changed to the Stage course for her second year and then worked in the theatre, mainly repertory, as an actor, stage manager and wardrobe mistress. After World War Two she made some appearances on the radio but returned home to Geldeston in 1952 and helped her elderly parents to prepare the results of their life-time of work for publication – especially the reports on the sites at Samaria-Sebaste, Ophel, and the relics of St Cuthbert in Durham that her mother had studied in the 1930s. In 1956 her one novel, The Brotherhood of the Cave, was published by Collins. Like Molly, Elizabeth became an acknowledged expert on ancient textiles and worked as a consultant for the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Ancient Monuments Laboratory, the Museum of London, and the archaeological services of East Anglia. In the 1970s, she helped save caches of ancient textiles from the new lake that had been formed in Egypt by the Aswan Dam, and she dated the Turin Shroud to the mediaeval period on the basis of its weave – a judgement that was confirmed in 1988 by carbon testing. Her many publications include work on mediaeval textiles and clothing, Anglo-Saxon gold braids and textiles, and Coptic liturgical vestments.

(iv) Diana Mary Rustat (“Dilly”) was born in the Sudan in 1918 and, together with her sister Elizabeth Grace, she attended the Farmhouse School, near Wendover, Buckinghamshire. From 1936 to 1940 she studied Natural Sciences at Somerville College, Oxford, and was awarded a 3rd in Moderations in 1938 and a 2nd in Geography in 1940 (BA 1942; MA 1950). From 1941 to 1946 she worked as an assistant editor at the Royal Geographical Society, where she edited Arctic, the Journal of the Arctic Institute of North America; and from 1955 onwards she edited Technical Series, the Arctic Institute’s series of special publications. In 1944 she married the distinguished archaeologist, explorer and civil servant Graham Westbrook Rowley (later MBE, CM) whom she had met at the Royal Geographical Society when he was giving a lecture on the crossing of Baffin Island, and the couple subsequently moved to Canada.

Graham Rowley was born in Manchester in 1912, educated at Giggleswick School, Settle, North Yorkshire, and Clare College, Cambridge, where he studied Natural Sciences and Archaeology from 1931 to 1935. After his graduation, the Curator of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology introduced him to Thomas Manning (1911–98), the leader of the British–Canadian Arctic Expedition, which, in the days before aerial photography, was preparing to explore, from 1936 to 1939, the largely unknown areas of Northern Canada round Foxe Basin, the shallow oceanic basin that is situated between Baffin Island to the east and the Melville Peninsula on the mainland to the west. Graham Rowley’s particular task, set by Diamond Jenness (1886–1969), the pioneer of Canadian anthropology who was at that time the Director of the Canadian National Museum in Ottawa, was to unearth evidence confirming the existence of a “Dorset Culture” in the Canadian Arctic that was quite distinct from the “Thule Culture” of mainland Canada that was discovered in 1921–23 by the Danish archaeologist Therkel Mathiassen (1892–1967). The expedition began its journey at the railhead of Churchill, on the west coast of Hudson Bay, in early May 1936 and then headed northwards to the south-west coast of Southampton Island, where it spent two months, allowing Rowley to collect artefacts that he found in ruined villages, en route to Foxe Basin, in the south of Melville Peninsula. The items collected by Rowley had once belonged to the remnant of the Sadlermiut Inuits, a group that had survived on remote islands in the Hudson Bay until 1903, when they were wiped out by disease. In mid-October 1936 the expedition travelled to Repulse Bay, on the mainland to the north of Southampton Island, and from here, in late December, Rowley and the ornithologist Reynold Bray (1911–38) proceeded northwards by dog-sledge for 250 miles to Igloolik, at the north-west corner of Hudson Bay, where Rowley undertook further archaeological investigations. In spring 1937, after a 300-mile journey by dog-sledge accompanied by a single Inuit helper, Rowley carried out more archaeological work between the two Inuit villages at Arctic Bay and Pond Inlet, on the northern end of Baffin Island at the northern end of Hudson Bay, thereby becoming the first white man to explore that part of Baffin Island and to cross the mountains from Steensby Inlet to Piling Bay. His most important finds were artefacts that dated back 2,000 years to the “Dorset Culture”, a Paleo-Eskimo culture that was much older than the “Thule Culture” of mainland Canada but was largely extinct by 1500, so that the Sadlermiut Inuits were believed to be its last surviving representatives. In September 1938, Rowley returned to Repulse Bay to continue his archaeological work, and in December 1938 he and two Inuit companions revisited Igloolik. They stayed here until February/March 1939, when they returned to northern Baffin Island where Rowley continued his exploration. But while he was in the south of Baffin Island in summer 1939, he found and excavated a major site at Avvajja, in the west of Igloolik Island (Dorset Island). The site was near the island’s southern tip, just off the Foxe Peninsula, and yielded artefacts that conclusively proved the existence of a “Dorset Culture”, and Rowley’s report on these finds was finally published in the American Anthropologist in 1946.

During his time in the Canadian Arctic, Rowley assimilated indigenous techniques of Arctic survival, learnt to speak Inuit, and helped to map the unexplored parts of the coastline of Foxe Basin, including several unknown islands, one of which now bears his name – as does a river on Baffin Island. When war broke out in 1939, he joined the Canadian Army, rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and was awarded the MBE. After the war, he stayed in the army for a year and organized Exercise Musk-Ox, the largest military exercise ever held in the Canadian Arctic (15 February–6 May 1946), the purpose of which was to test men, vehicles and equipment under Arctic conditions. After his demobilization in 1946, he worked for five years with the Canadian Defence Scientific Service in Ottawa, where he was responsible for the co-ordination of military research in the Arctic in the context of a possible incursion by the USSR, and from 1946 to 1953 he initiated further expeditions of exploration to the northern end of Hudson’s Bay. In 1947 he, with his wife Diana and a group of friends, founded the Arctic Circle Club, whose journal is the Arctic Circular.

From 1951 to 1975 Rowley worked for Canada’s Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources and was closely involved in the planning and setting up of the Igloolik Resource Centre, which opened in 1975. An obituarist wrote that he “possessed an exceptionally sharp analytical mind, and cultivated a wide range of contacts both in and outside government. By this means he acquired an almost unrivalled knowledge of the workings of the Federal Government and of the internal politics involved.” So it is perhaps not surprising that from 1981 to 1986, i.e. after his retirement from the Civil Service in 1974, he became Research Professor of Northern and Native Studies in the Canadian Studies Program at Carleton University, Ottawa. He received many medals and public honours, including the Canada Medal, the US Arctic and Antarctic Service Award, the Northern Science Award, and, in 1963, the prestigious Massey Medal of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. He also published two major books on the Canadian Arctic: The Circumpolar North (with G.W. Rogers) (1978) and Cold Comfort: My Love Affair with the Arctic (1996). His daughter Susan Rowley is now the Curator of Archaeology at the Museum of Anthropology and an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and she continued archaeological work on Igloolik, enthusiastically supported by both her parents.

****************************************************************************

Charles Ivor Sinclair Hood (“Ivo”)

Ivo’s wife and son

Much of our information about Ivo Hood comes from the manuscript biography written by his wife, Christobel (“Kit”) Mary (later JP, MBE) Hoare (1887–1960) (m. 1916). She came from a family that was socially similar to, albeit wealthier than, Ivo’s, being the seventh and youngest child of Samuel Barclay Hoare [III] (1841–1915) (1st Baronet from 1899), the Conservative MP for Norwich from 1886 to 1906, and Katherine Louisa Hoare (née Hart-Davis) (1846–1931) (m. 1866).

Samuel Barclay Hoare [III] was the great-grandson of Samuel Hoare, Jr [I] (1751–1825), a wealthy Quaker, a leading opponent of the slave trade, and one of the 12 founding members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1787), which achieved its abolitionist aims in 1807. In c.1765 Samuel Hoare, Jr was apprenticed to Henry Gurney (1721–77), a woollen manufacturer of Norwich, and in 1776 he married Sarah Gurney (1757–83), the eldest daughter of Samuel Gurney (1723–70), a member of the successful Quaker banking family that established Gurney’s Bank in Norwich in 1775. In 1896 this was one of the several banks that merged to form Barclays Bank. Sarah Hoare died ten days after the birth of their son Samuel Hoare [II] (1783–1847) and in 1788 Samuel Hoare, Jr [I] married Hannah Sterry (c.1769–1856).

Starting in 1803, Samuel Hoare [II] learned banking in Lombard Street, in the City of London, EC3, and in 1806 he married his second cousin Louisa Gurney (1784–1836), the seventh of the 11 children of John Gurney (1749–1809), who had inherited Gurney’s Bank, and Catherine Gurney (1754–92) (née Bell). Louisa was well-known for being passionately concerned with education, especially the education of young children, and wrote several books on the subject; she was also a sister of the Quaker prison reformer Elizabeth Fry (1780–1845). The two girls spent much of their childhood at Earlham Hall, a building that goes back to c.1580 and is situated about three miles west of Norwich. It was leased to the Gurney family in 1786 and they lived there until 1925, when it was acquired by Norwich City Council. In 1963 it was leased to and became the central building of the newly founded University of East Anglia, and since then it has been extensively restored and modernized, and now serves as the home of UEA’s School of Law.

Christobel’s six siblings were:

(1) Muriel Annie Caroline (1867–1937), later Press after her marriage in 1896 to Edward Payne Press (1870–1914); Press was a successful Bristol solicitor who, in a fit of depression and general worry, committed suicide on 5 February 1914 by lying down on the railway line near Clifton Bridge Station, where he was decapitated by a train (see two articles in the Bristol Times & Mirror, 5 and 7 February 1914);

(2) Annie Louisa (1868–1951), later the Mother General of the Community of St Mary Magdalen, Wantage;

(3) Elma Katie Hoare (1871–1958), later Paget after her marriage in 1892 to the Right Reverend Henry Luke Paget (1853–1937);

(4) Marjorie Gurney (1876–1931);

(5) Sir Samuel John Gurney, GCSI, GBE, CMG, PC (1880–1959); married (1909) Maud Lygon (1882–1962);

(6) Oliver Vaughn Gurney (1882–1957); married (1906) Phoebe Alice van Neck (1885–1906).

Samuel John Gurney Hoare, Christobel’s most distinguished sibling, was an alumnus of New College, Oxford, served in World War One from 1916 to 1918 and reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. In 1944 he was made the 1st (and only) Viscount Templewood of Chelsea, the borough of which he had been the Conservative MP from 1910 to 1922 – though the name Templewood derives from the name of a house in Sheringham, Norfolk. A professional politician, he enjoyed a brilliant career under several prime ministers that started when he was Secretary of State for Air from 1922 to 1929; he maintained his interest in aviation by being an Honorary Air Commodore in the Auxiliary Air Force from 1930 to 1957. He was Secretary of State for India from 1931 to 1935, becoming an opponent of Winston Churchill in the process; from June to December 1935 he was Foreign Secretary and concluded the Hoare–Laval Pact with France that granted Mussolini’s Italy considerable and unpopular concessions over Abyssinia; from 1936 to 1937 he was the First Lord of the Admiralty and oversaw the belated expansion of the Royal Navy and the development of the Fleet Air Arm independently of the Royal Air Force; from 1937 to 1939 he was a reforming and liberal Home Secretary who tried to get the death penalty abolished and negotiated approval for the Kindertransports that brought Jewish children to Britain from Nazi-occupied Europe; and finally, from 1939 to May 1940, he was Lord Privy Seal. But being one of the foremost supporters of Neville Chamberlain (Prime Minister from May 1937 to 10 May 1940) and his policy of appeasement, he was dropped from the Cabinet once Churchill succeeded Chamberlain on 10 May 1940, and after a period of inactivity served as the British Ambassador to Spain from 1940 to 1944. During the post-war years he was active in many public spheres, and although he died in London, he is buried in the graveyard of Sidestrand Parish Church, north Norfolk.

Sidestrand is a village on the north-east Norfolk coast, about three miles south-east of Cromer, where Samuel Hoare [II] was born in 1783. In the early nineteenth century the town became so popular among the well-to-do as a resort that some of the rich Norwich banking families made it their home, and in Chapter 12 of Jane Austen’s Emma (1815), the terminally hypochondriac Mr Woodhouse cites his favourite apothecary Mr Perry as holding Cromer “to be the best of all the sea-bathing places” because of its “fine open sea”, “very pure air”, and comfortable and convenient lodgings. Certainly, Samuel Hoare, Jr [I] holidayed in Cromer with his second wife and family at about this time, for Hannah had relatives there, and at some point between 1871 and 1881 their descendants moved from 2 Hyde Park Street, Paddington, London W2 to the Cliff House, Mundesley Road, Cromer. Indeed, they liked it there so much that at some point during the next 20 years they renovated an old house on the cliff at nearby Sidestrand that was called or became known as Sidestrand Hall, and lived there until at least 1911.

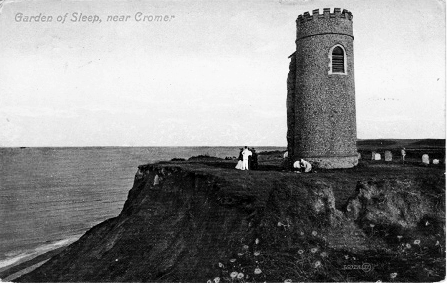

By the end of the nineteenth century, the nearby parishes of Sidestrand and Overstrand had also become so popular that Overstrand was known as “Millionaires’ Village”. But Overstrand’s medieval church of St Martin’s was a ruin by the eighteenth century, and St Michael’s Church, Sidestrand, was beginning to crumble by the 1840s and threatened to fall into the sea. This moved Christobel’s father to have a copy built, largely at his own expense, incorporating some of the original and consecrated in 1881, that was further back from the coast. The two livings were separated in 1910, when the Reverend (later Canon) Lawrence Carter Carr (1861–1948) gave up the better endowed living of Sidestrand and retained just the Overstrand one. Then in 1916, i.e. after the death of Sir Samuel Barclay Hoare of pneumonia on 20 January 1915, his elder son Samuel John Gurney Hoare, the 2nd Baronet, presented the vacant living to his new brother-in-law, Ivo Hood, who became the Rector there in November 1916, soon after his marriage to Christobel on 14 October 1916. Sidestrand Church has inspired two poems: ‘The Garden of Sleep’, by Clement Scott (1841–1904), and ‘The Deserted Church Tower’, by Ralph Hale Mottram (1883–1971), who is best remembered for his World War One trilogy of novels entitled Spanish Farm (published 1924), and Sidestrand Hall is now a school that caters for children with a wide range of special educational needs.

The parish church of St Michael was one of Norfolk’s round-tower churches, but as it was situated dangerously near an eroding coastline, it was removed stone by stone in 1880 – apart from the round tower, which remained in the churchyard on the cliff – and rebuilt on its present site but with a modern tower; the original tower, which is depicted in the upper illustration, finally fell into the sea in 1916.

Christobel devoted her earlier years to local history and antiquarian research, and her later years to local government. Her first interest led her to publish several historical and antiquarian monographs (see the Bibliography below), including historical studies of Sidestrand (1914) and Gimingham (1918), and many papers on similar topics in learned journals; she was made a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. But as someone who was deeply involved in local government, for services to which she was awarded the MBE in 1956, she became particularly interested in housing, probation work, and the care of children, and was a JP, a member and alderman of Norfolk County Council, and Chair of Erpingham Rural District Council.

Christobel and Ivo had a son, Richard Ivor (1917–30), who became a pupil at Taverham Hall School, Norfolk (founded in 1920 and now part of Langley Preparatory School at Taverham Hall). Richard died after contracting meningitis as a complication of German measles and left £545 10s. 8d. (£24,977 in 2017).

Ivo’s education and early professional life

In her biography of Ivo, Christobel notes that when he looked back to his childhood in rural Lincolnshire, he often told her “of the joy it used to be to him and to the others to go round the farm and estate with their father, to watch him play cricket or to hear him read the lessons in Church”. She also notes that after their marriage, Ivo was always recalling little things which his father had told him as a child but which he had forgotten until life in rural Norfolk revived them. Like Alban and Martin, Ivo was musical and he, too, held a music scholarship at Llandaff Cathedral Choir School (see above), from c.1893 to 1900. From 1900 to 1905, he attended Haileybury Imperial Service College, where he was a member of Edmonstone House. He did well in his schoolwork and was reasonably good at games, keeping wicket for his House and playing in the House Football XI. He was also a member of the Debating and Natural Science Societies, became Secretary of the Antiquarian Society (1903–05), organized some excellent part-singing, and was made a College Prefect in his final year.

This uncaptioned photo of Ivo sitting on a wall during his time at Haileybury College comes from Christobel’s manuscript biography.

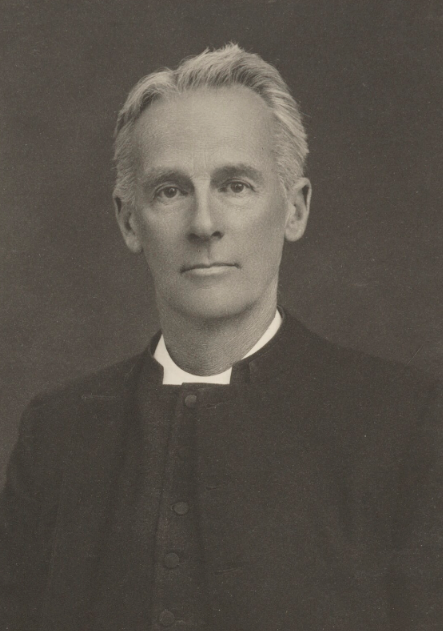

While Ivo was at Haileybury, the Reverend Dr the Hon. Edward Lyttelton (1855–1942) was its Headmaster from 1890 to 1905, when he became Headmaster at Eton. Christobel tells us that:

Ivo’s regard for him was very great and in the development of his religious ideas he owed much to his teaching. Even in boyhood Ivo’s nature was most spiritual and […] he came to [Haileybury] filled with a desire for Holy Things[,] and in Edward Lyttelton’s sermons he found much food for thought [because] the Head’s spiritual and ethical teaching was both congenial and stimulating to him.

Nevertheless, like many other people, he found “that as a man, Dr Lyttelton was often very annoying and both unobservant and unsympathetic in his dealings with human beings. Nothing, however, could alter [Ivo’s] affectionate respect for his old Headmaster”, who would succeed him as Rector of Sidestrand from 1918 to 1920.

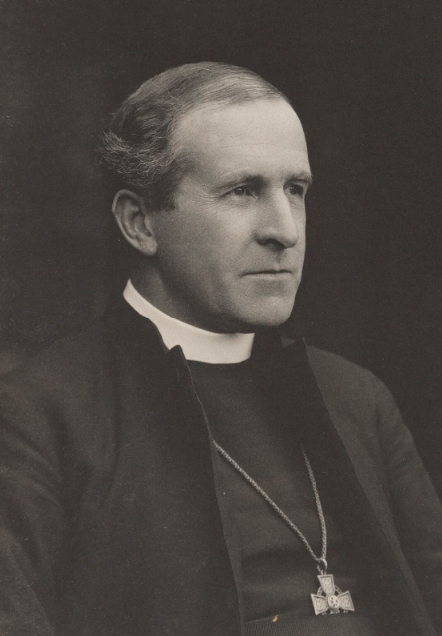

The Hon. Edward Lyttelton, photographed in c.1916 by Walter Stoneman, for James Russell & Sons

(© National Portrait Gallery, London: NPG Ax39175)

As reading was Ivo’s greatest interest, he got though an enormous number of books while at Haileybury, passed Responsions in the Lent Term of 1905, and was awarded a Leaving Scholarship. He followed Alban to Magdalen. During his interview there in December 1904, he gave a long and ardent defence of Cardinal Wolsey’s Church policy, but was dismayed to discover afterwards that he had been doing so before C.R.L. Fletcher (1857–1934), Magdalen’s first Fellow and Tutor in Modern History (Tutor from 1883 to 1906, Fellow from 1889 to 1906), who was notorious for his disapproval of the great Cardinal. Fletcher was also well-known for being a committed imperialist and a Protestant Anglican with “controversial” views on foreigners and democracy. However, he conceded that Ivo’s defence of Wolsey was unusual and well-presented and was one of the four examiners who recommended him to Magdalen’s Tutorial Board on 21 December 1904 for election to the College’s one History Demyship, when he was named as the best of eight candidates for a place to read History, of whom four were successful.

Ivo matriculated at Magdalen on 14 December 1905, but the College’s records show that his subsequent academic performance did not fulfil his initial promise. Nevertheless, they also show that throughout Ivo’s time at Magdalen, President Warren consistently awarded him an alpha grade in the College’s termly examinations – known then, as now, as Collections. That said, it needs to be remembered that Warren gave this grade to all those Magdalen undergraduates whom he considered “good College men” – i.e. decent young chaps who had found their proper place within the institution and were doing something positive on its behalf. During the Lent Term of 1906, Ivo passed the First Public Examination (on the Holy Scriptures) without any difficulty, but Magdalen’s records strongly suggest that by the start of the same term he had changed from History to Classics, a change of course that caused his academic performance to deteriorate so badly that of the 13 grades that his tutors awarded him during the remaining four terms leading up to Classical Moderations, ten were gammas or deltas, two were betas, and only one showed any trace of alpha quality. He was awarded that grade for his performance in Logic by the Reverend James Thompson (1878–1956; Fellow 1904–56), Magdalen’s controversial Dean of Divinity, whose ultra-modernist, ultra-rationalist Miracles in the New Testament (1911) caused the Bishop of Winchester to deprive him of his licence to hold a cure of souls and nearly cost him his Fellowship. So it is not surprising that when Ivo took Classical Moderations in April 1907, he achieved only a fourth – the grade above “fail”. Despite that result, the College did not deprive him of his Demyship, as it could have done, and in May 1908 it gave him leave to stay at Magdalen for a fourth year without demur. Having achieved a third in Greats (the final exam in Classics) in Trinity Term 1909, Ivo took his BA on 17 December 1909.

In c.1902/3, while Ivo was going through the second half of his education, Christobel’s family began spending winters on the French or Italian Riviera, and her biography dates her first meeting with Ivo during his holidays between leaving Haileybury and going up to Oxford (i.e. in 1905):

He was out at his mother’s villa at San Remo, and I and my parents were at a hotel for the winter. I already knew Molly and Dorothy, and during the holidays the party was increased by the arrival of Ivo, Alban [and some of her friends]. We had a very jolly time that holidays [sic] with walks into the hills and games of hockey and tennis at the Sports Club – besides a good deal of choir singing for those blessed with voices.

As Christobel was much younger than her siblings (see above), she was particularly attracted to the large Hood family and wrote in her biography:

It must have been an ideal family to belong to, with all the children so near together in age and all of very kindred tastes and affections. I can find myself enjoying the jolly party at Nettleham, for I was very much alone in my childhood owing to my being so many years younger than my brothers and sisters. […] I began by falling in love with the whole Hood family[,] but gradually Dorothy and I singled each other out as especial friends, and it was not until later on that Ivo and I “found each other”. From the very first, however, we were very close friends and had very many tastes in common, and I was never so happy as when I was with him or Dorothy.

So as the Hoares, like the Hoods, returned to San Remo every winter, “each year saw the ties between my family and Ivo’s grow closer and closer!”

Music was a major bond between the two families and Christobel remarks that:

all through his life, Ivo shared the [Hood] family love of music, and although he could not play the organ and the piano like his mother and Alban and Dorothy, yet he was full of music, with a sweet singing voice, and a real capacity for playing even though he lacked execution. In London we often went to music together – I remember in particular a wonderful performance of Götterdämmerung in May 1912 [5 and 13 May 1912 in Covent Garden]; the 5th Beethoven Symphony at Queen’s Hall in the winter of 1912 [30 November 1912 with Sir Henry Wood conducting] […] and the 7th Symphony at Bournemouth in 1915. He specially loved the Scherzo of the 7th, and another of his great favourites was the Dvořák New World Symphony – he loved to imitate the jolly bassoon part which runs all through it.

Christobel also observes that in Oxford, Ivo “found his mind’s true home” – which is odd given his academic performance described above – but amplifies this by explaining that she didn’t “think anyone could have been happier than he was during his years at Magdalen, where he made a host of life-long friendships. […] He loved his fellow men, and friendship and friendliness were a delight to him.” Moreover, in her biography Christobel identifies seven Magdalenses as Ivo’s particular friends, of whom five were killed in action during World War One: Robert Menteth Bailey (1882–1917), Edward Vivian Dearman Birchall (1884–1916), John Leslie Johnston (1885–1915), the Hon. Charles Thomas Mills (1887–1915), and Algernon Hyde Villiers (1886–1917). All of these stand out because they were socially or politically conscious – in some cases both – and because none of them can be described as a “boatie”, a “hearty” or a “blood”, even though all of them enjoyed some kind of sport, even rowing.

It was also during his time at Oxford that Ivo first visited Norfolk. On the first occasion he stayed at Brancaster in order to read and play golf, from where he motored over to see Blickling Hall, and he spent a second Norfolk holiday on the Broads. Christobel wrote:

he did love Norfolk, and after Nettleham was let and Lincolnshire was no longer his home, Norfolk seemed to fill its place in his affections. His mother spent several summers at Sidestrand or Overstrand (see above), and I think that Ivo loved Sidestrand more each time he came. We rode a great deal on the shore – mostly Ivo and me – though sometimes Dorothy, Molly or Martin came too.

The Magdalen College Mission was founded in 1884 and was located at Portsea, Hampshire, from 1896 to 1908. But in 1906 the College began considering moving it to London, and according to Christobel, Ivo “had not been very long at Magdalen” before he and the Revd James Thompson went to London to find a district in which it could make its new home. So given what has been said above, it is probable that Ivo and Thompson “clicked” after Ivo had changed from Modern History and during the time when Thompson was teaching Ivo Logic and discovering that his pupil not only had some ability in that subject but was also considering ordination (see below). So probably at some time between late February and early May 1907, Thompson probably invited him to accompany him on an exploratory visit to London, where they reconnoitred Somers Town, a notorious slum area that was just behind Euston Station and had got its name when Charles Cocks, the 1st Baron Somers of Evesham (1725–1806), acquired it in 1784. By the end of the nineteenth century, Somers Town was known as “the foulest parish in all London” and it was this that persuaded Thompson and Ivo that it was “an ideally beastly spot” for the Mission. But Christobel also says that the parish claimed Ivo’s heart “from the first, and from the first the very rough people of Somerstown took him to their hearts”, a symbiosis which caused Ivo to begin working there from time to time even while he was still an undergraduate. All of which suggests a reason why Ivo, unlike E.H.L. Southwell, the bright young Classical Demy whose academic performance at Magdalen declined when he became a born-again boatie, was never carpeted for his poor academic performance. President Warren, who was a devout churchman, was deeply committed to the education of the poor and underprivileged. Unlike some Heads of House in Oxford, such as his old Tutor, Benjamin Jowett of Balliol College (1817–98; Fellow and Tutor 1842–98; Master of Balliol 1870–98), Warren did not consider academic performance as the be-all and end-all of an Oxford education on the grounds that “a single-minded emphasis on developing the mind could easily make a student narcissistic” and that “learning was only of value if it promoted a greater cause”. Consequently, he would have thought that Ivo’s interest in the Somers Town Mission meant that he had discovered his proper place in Magdalen’s collective life, but was also preparing himself for his future life in the Kingdom of God, British society, and the British Empire, three realms which, for Warren, were pretty well coextensive.

After the new Magdalen Mission was established in Somers Town in 1908, with its headquarters at 1 Oakley Square, Ivo worked there for 18 months during 1909 and 1910 since, according to Christobel, he had been considering ordination for a very long time. And although she did not think that his intention of doing so ever really wavered, she does record that in the early years of their relationship, “he sometimes felt himself being drawn into philosophic speculations which made him doubt his own orthodoxy” – probably the result of being taught philosophy by Thompson and having to cope with his Modernism. But she adds that Ivo was not in any hurry to become a priest, so that his brother Martin, now a Sub-Lieutenant in the Navy, once said: “I shall be an Admiral before you’re even a beastly little curate!” So from 1910 to 1911 Ivo trained for ordination at Cuddesdon Theological College, near Oxford, whose Principal was the father of John Leslie Johnston, and although Ivo had a special affection for Canon Johnston, Christobel records that he did not find his time at Cuddesdon “really congenial” and that it “gave him very little help in the finding of his vocation”. Finally, on 24 December 1911 (the fourth Sunday in Advent), Ivo was ordained deacon in St Paul’s Cathedral by Arthur Winnington-Ingram (1858–1946), the Bishop of London from 1901 to 1939, who was already very prominent in social work in the East End of London but would become a notoriously jingoistic supporter of the Great War. Christobel was able to attend the service and was of the opinion that Ivo “looked pale and rather troubled – quite different to the strength and happiness of his face at his ordination as Priest on the same Sunday a year later”.

Ivo then became the curate of the spectacularly ugly Church of St Mary the Virgin (built in 1852 in Eversholt Street, NW1), the Anglo-Catholic parish that included the Magdalen Mission, and his first task as a deacon was to assist at the service of Holy Communion on Christmas Day, the day after his ordination. From 8 to 20 April 1911 Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (aka Lenin) lived at 6 Oakley Square because of its proximity to the Reading Room at the British Museum, so missed being one of Ivo’s parishioners by a mere eight months. In spring 1912 Ivo took over as Missioner – the Head of the Magdalen Mission – from the Revd Lumley Cecil Green-Wilkinson (1878–1949; Magdalen 1897–1902; MA 1904), who had held this post since 1908, and he remained as Missioner until 1916, earning a stipend of £180 p.a. for his pastoral work.

Lumley Cecil Green-Wilkinson, as Borachio in the Oxford University Dramatic Society production of Much Ado About Nothing in May 1901

(Photograph courtesy Magdalen College)

Ivo was motivated to do such work rather than accept a comfortable and lucrative country living, because he felt very deeply about “the needs of his country”, whether spiritual or social. In the printed report on the Mission’s activity in 1913 that he prepared for its Annual General Meeting in 1914, he said, with Somers Town in particular in his mind, that “these great problems of the poverty, the overcrowding, and the inhumanity which persist alike in the town and in the country are things which we are the last people in the world to dare to neglect”. The phrasing of this statement is oddly ambivalent, for it is not clear whether Ivo is simply thanking and praising his friends and co-workers for helping him to address these “great problems”, or reproving the British establishment, of which he and most of his friends and helpers were a part by virtue of their work and privileged education, for being “the last people in the world” to perceive and address them. We shall find a similar ambivalence in what he has to say about the Great War.

However one understands the above statement, Ivo was determined to do at least something about the situation of Somers Town, and Christobel was in no doubt that his life as a Missioner in Somers Town was “very busy” and “very hard”, not least because Magdalen College House “was a real centre of activity, enthusiasm and thought […] that was usually full of Magdalen men, past and present [–] some actually living there, others (the Prince of Wales amongst them) turning up for meals and clubs and talk”. So when Ivo came in,

from a long day’s work in the parish or at Health Committee, and an evening at the Clubs [see below], he would find his friends at Oakley Square awaiting him and ready to talk and argue for half the night, [and] when at last they went to bed, he would write letters […] and then go to an all too short night in bed, rising early next day for the daily Celebration at St Mary’s.

Besides his church, Ivo was also said to be “most useful in municipal and such work”, did a lot towards setting up the St Pancras Dispensary at the top end of Oakley Square – “most excellent it is, an immense help to our people” – and was involved in the Workers’ Educational Association, which brought him into contact with its co-founder, the teacher Albert Mansbridge (1876–1952).

Ivo’s printed report for 1913 amplifies the above remarks and contains many illuminating details which confirm that Ivo and his co-workers had many calls on their time. They took over a men’s club, probably the Church of England Men’s Society, which, before the Institute was available, was mainly a discussion group that met once a week in a local coffee house. They also took over a boys’ Bible class that met on Sundays and also ran four other clubs for boys. One of the four was for small boys who were still of school age and was called “Happy Hours”. It was open on four nights a week from 3.30 to 6.30, had about 80 members, organized holidays that enabled “twenty boys of very poor families who otherwise would have had no holiday at all to spend a fortnight on the hills above West Wycombe”, and took the older members to the “Skilled Employments Exhibition” in order to persuade them “to try and get better jobs on leaving school”. Then there was the Waynflete Club which was aimed at boys between 15 and 19, numbered 50 members, organized games of football (which were very popular), and put on plays. In summer 1913 Ivo organized an eight-day camp in Oxford in a field near Magdalen’s sports ground, bordered on the River Cherwell, and had a “fleet of punts” at its disposal. The third club, consisting “of boys who have been with us for some time but who are still too young for the Waynflete” taught its members “the mysteries of First Aid, which we hope may be a prelude to further instruction in Health matters”. And the fourth was an essay society, which ran for a few weeks only as the Mission’s educational activities had, on the whole, been “rather less successful”. Then there were the events that were run for the local “coalies”, i.e. men who were employed, often casually and for a minimum wage, “in the vast underground depots” of which there were many in Somers Town, being situated as it was near two large railway stations:

The men were invited to come at first one evening a week, to play cards or other games, sing or smoke. At the end of the evening we had prayers and sang some hymns. Those who came pledged themselves to keep off strong drinks, to say the Lord’s Prayer every day and to come to church on Sunday. If anyone failed, the others were to give him a bad time!

They were also taken on trips to the country and provincial towns like Oxford, and when they “petitioned for another night’s entertainment a week”, a young woman

kindly came and tried the experiment of forming a singing class, which has been a most unqualified success. All kinds of songs […] have been learnt in chorus[,] and when [they are] well known [they] become adopted by one or other member as their own, so that we can now give quite a number of solos as well as our concerted pieces.

Four of the coalies were confirmed in St Paul’s Cathedral and Ivo commented that it was good to find members of this group “planning outings for their families or sporting clothes or watches with evident pride that they are not spending their money in other less profitable ways”. When war broke out, Ivo started a Boy Scouts group, drilled Volunteers in the new Institute (see below), and got a rifle range fixed up on behalf of the war effort.

Women co-workers – who formed the Ladies Association – were also active on behalf of the Mission. They liaised with local schools, the local Health Authorities, the Charity Organization Society, and “many of the other Societies working in St. Pancras”. When the St Pancras Borough Council closed all one side of a local street as “unfit for human habitation”, a housing expert was brought in to improve some of the properties, which some of the Ladies Association’s members undertook to manage according to the principles of Miss Octavia Hill (1838–1912) – an English social reformer who had recently died in Marylebone, not far from Somers Town, and who had worked tirelessly for half a century on developing housing in the slum areas of London and conserving such green areas as Hampstead Heath. She was a fierce opponent of bureaucratic interference and misplaced charity in the struggle to remedy working-class poverty, and one of her central principles was a stress on self-reliance. During 1913, the Ladies Association had increased its workload and Ivo commented that as there was “really no department of the [Mission’s] work which does not benefit from its co-operation”, it was becoming “more and more difficult to distinguish [the Association’s] activities from those of the rest of the Mission”. It also ran an “Old Girls’ Club”, whose speciality consisted in learning and singing part songs and choruses which “provided many excellent items in the programme of the Christmas Concerts” and whose members were taken on trips to the countryside. Then there was a Senior Girls’ Club, for girls between the ages of 14 and 20, which was said to be “very flourishing” and had “contributed the first dramatic entertainment ever conducted by any of the clubs at Christmas”. It also offered a “drilling [gymnastics] class” every Thursday night, as did the Junior Club, for girls between the ages of 8 and 14, which had started in 1913 and offered classes in dancing as well as gymnastics. There were also the “Three Meetings for Somers Town Mothers”, which organized a holiday in the country near Leatherhead, Surrey, for 14 mothers from the parish, and a “Girls’ Class”, whose function is not explained in the report, and during 1913 two members of the Association formed a band of Girl Guides. The author of this part of Ivo’s report noted that it was “very satisfactory to record that many of the girls were able to have holidays of a week and more in the summer” and that over 20 members “were aided to see some real country by the Oxford Ladies Holiday Fund”.