Fact file:

Matriculated: 1901

Born: 21 August 1882

Died: 1 December 1917

Regiment: East Riding Yeomanry

Grave/Memorial: Cairo War Memorial Cemetery: O.44

Family background

b. 21 August 1882 at Coates Lodge, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, as the eldest child and only son of Henry Bailey, DL (1822–89), and his second wife Christina Bailey (née Thomson) (1849–96) (m. 1881). Henry Bailey already had two sons and a daughter by his first marriage (1848) to Mary Louisa Bailey (née Puleston) (1826–65). At the time of the 1881 Census, Henry was living at Coates Lodge as a widower (six servants); at the time of the 1891 Census, Henry and his new family were still living at that address (six servants). In the mid-1890s, the family was living at 35, Harley Street, Cavendish Square, London. After Robert was orphaned, he lived at Achray, Callander, Perthshire, Scotland.

Parents and antecedents

Henry Bailey was the youngest (eighth) child and fifth son of Sir Joseph Bailey (1783–1858), from 1852 the 1st Baronet of Glanusk Park, Crickhowell, Powys. At the time of the 1861 Census, Henry Bailey described himself as a farmer in Denbighshire, North Wales, but field sports seem to have been his real passion.

Sir Joseph Bailey, a farmer’s son from Wakefield, Yorkshire, became one of the great ironmasters of South Wales. While in his teens, he is said to have tramped from Yorkshire to Merthyr Tydfil to find work with a rich uncle, Richard Crawshay (1739–1810), the famous ironmaster of nearby Cyfarthfa. By hard work and dedication he soon acquired a good grasp of the iron industry and coal-mining, and on his uncle’s death he inherited a quarter share of the Cyfarthfa iron-works, by now the biggest in the world, which he sold in 1813 for £20,000 in order to buy the defunct Nant-y-glo (= Brook of Coal) iron works, in Monmouthshire, which he restored. Production and exports increased, even during the slump year of 1816, and when Joseph was joined at Nant-y-glo in 1820 by his younger brother Crawshay Bailey (1789–1872), the two brothers developed Nant-y-glo into one of Britain’s greatest iron-works. By 1823 they had five blast furnaces in operation and added two more in 1826–27; they also acquired the Beaufort iron-works in 1833 for £45,000. After amassing a large fortune and becoming one of the richest men in Britain, Joseph retired in 1830, handed over management of the works to Crawshay Bailey. He bought estates in several Welsh and English counties, including Glanusk Park, near Crickhowell, Breconshire, where he lived until his death. He became High Sheriff of Monmouthshire in 1826, the year when he bought Glanusk Park, and Conservative MP for Worcester (1835–47) and Breconshire (1847–58). He left c.£600,000 (c.£35,000,000 in 2017).

Henry Bailey’s first wife was the daughter of Sir Richard Puleston (1789–1860), 2nd Baronet of Emral, Plas-y-mers, Hafod-y-wern, Llwynycnotiau and Carnarvon, all properties scattered over North Wales, a prominent figure in Flintshire and its High Sheriff in 1844. The Pulestons were an ancient Welsh family who can be traced back at least as far as the late thirteenth century, and Sir Roger de Puleston (d. 1294) was the first member of the family to live at Emral Hall, a moated house in Flintshire. The Puleston family lived there more or less continuously until the early 1900s, when, after disastrous fires in 1895 and 1904, it was sold to the Summers family, who in their turn sold it in 1936, when the Hall was demolished. The baronetcy became extinct with the death of the Reverend Sir Theophilus Gresley Henry Puleston, the 4th Baronet, in 1896; and when the heir to the estates, Henry Augustus Bailey (1850–96: Robert’s half-brother), died soon after the 4th Baronet, the estates passed to his younger brother Crawshay Wellington Bailey (1853–1935) (q.v.), who died childless.

Henry’s second wife, Christina, i.e. Robert Bailey’s mother, was the daughter of Neale Thomson (1807–57), 4th Baron Thomson, a rich cotton-goods manufacturer whose family firm, Robert Thomson & Son, Cotton Spinners and Power-Loom Cloth Manufacturers, had been founded by James Thomson (1742–1820), Neale’s grandfather, at the Adelphi Cotton Works in Hutchesontown, Glasgow (part of the Gorbals district to the south of the River Clyde). Neale took charge of the works in 1833/34, after the death of his two elder brothers, and ran it until his death: the firm was dissolved on 30 June 1882. In 1798, the Thomson family acquired Camphill, in Renfrewshire, just south of the city boundary, and it was here that Robert Bailey’s mother was born in the fine Palladian house designed by her grandfather Robert Thomson (1771–1831), a friend of the Scottish historical novelist Sir Walter Scott (1771–1852) and the leading Scottish portrait painter Sir Henry Raeburn (1756–1823). In contrast to Joseph Bailey, i.e. Bailey’s paternal grandfather, who was hated by the local Welsh for his hard-nosed capitalism and deployment of the militia to break up strikes, Neale Thomson, Bailey’s maternal grandfather, was well-known in Scotland as a generous, warm-hearted and sagacious philanthropist who took great interest in and great care of his work force. The philanthropic trait emerged in Neale’s grandson Robert, who also resembles him facially and whom Michael Bloch has recently, and rightly, described as “kind, generous, profoundly Christian, good-humoured, scholarly, clever and wise”.

Neale Thomson (1807–57): Bailey’s maternal grandfather

Siblings and their families

Half-brother of:

(1) Henry Augustus (1850-96);

(2) Elizabeth Maria (1851–1917); later Gregory after her marriage in 1881 to George Francis Gregory (1856–1902); one daughter;

(3) Crawshay Wellington (Puleston from 14 April 1904) (b. 1853, d. 1935 in The Grand Hotel, Ostend, Belgium); married (1889) Edith Elfrida Bacon (1858–1946).

Brother of:

(1) Helen Christina (“Teenie”) Bailey (1884–1962); later Lees-Milne after her marriage in 1904 to George Crompton Lees-Milne (1880–1949); two sons, one daughter;

(2) Margaret Doreen (“Deenie”) (1887–1952); later Cuninghame after her marriage in 1912 in Scotland to William John Cuninghame (b. 1880 probably near Ayr in Scotland, d. 1919); William died on 19 March 1919 in Cologne of influenza, aged 39, while serving as a Major in the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry, the South Nottinghamshire Hussars (Territorial Force); he was buried in Cologne Südfriedhof [Southern Cemetery], Grave I.F.9.

Henry Augustus Bailey was commissioned Lieutenant in the 29th Foot (later the Worcestershire Regiment).

George Francis Gregory, JP, was the son of George Burrow Gregory (1813–93), a leading London solicitor and Conservative MP for East Sussex (1868–85), then East Grinstead (1885–86). Educated at Eton and Cambridge like his father, George Francis was a member of the Inner Temple and had a successful career as a barrister on the South-eastern Circuit. From 1891 until her death, his wife Elizabeth Maria was committed as insane to Wonford House Hospital, Exeter, Devon. Their only child, Christian Teresa Gregory (1883–1945) married (1910) Harold Edward Hewitt (later Major) (1878–1944).

Crawshay Wellington, JP, was a man of independent means and at the time of the 1891 Census he was living in Sulhampstead, seven miles west-south-west of Reading. At some point in his life, he lived at Emral Hall, Flintshire, the family estate of the Pulestons, his mother’s family. But from 1902 to 1904, when, on 14 April, he changed his surname from Bailey to Puleston by royal licence, he lived at Worthenbury Manor, on the border between Cheshire and Flintshire. This was the village about seven miles south-east of Wrexham where his uncle, the Reverend Sir Theophilus Gresley Henry Puleston, had been Rector from 1848 until his death in 1896, leaving no children. After World War One, Crawshay and his wife moved to the Villa Beatrice, Ave. de Grande Bretagne, Monte Carlo, in the Principality of Monaco.

Helen Christina Lees-Milne was a well-known beauty and is seen here driving the smaller, open-top car that was made by Ford and known as a “Tin Lizzie”

Helen Christina Bailey’s husband, George Crompton Lees-Milne, was the son of James Henry Lees (1847–1908; Lees-Milne from 1890), an energetic and successful Lancashire industrialist who had inherited the fortunes of two Lancashire cotton-spinning families – the Milnes and the Cromptons – and then, in 1904, turned himself into a country gentleman by acquiring the Ribbesford estate in Worcestershire. After Helen and George’s marriage, they moved first to Crompton Hall, near Oldham, Lancashire, and then, in 1906, to Wickhamford Manor, a fine half-timbered house in a beautiful garden near Evesham, Worcestershire. In his autobiography Another Self, their son, (George) James Henry Lees-Milne, leaves a wonderfully graphic and very amusing picture of the strange relationship between his vague, absent-minded and very attractive mother and his eccentric, hidebound, sports-obsessed, and anti-intellectual father – who left £110,333 (c.£2,000,000 in today’s values). Their daughter (oldest child) Audrey (1905–99) married (1931) Matthew Arthur (1909–76), the 3rd Baron Glenarthur (one daughter; marriage dissolved in 1939); their older son (second child) (George) James Henry (“Jim”) married (1951) Alvide Viscountess Chaplin (1909–94); their younger son (third child) Richard Crompton (“Dick”) (1910–84) married (1936) Elaine Joyce Brigstoke (1911–84), the daughter of a family that had settled in Kenya, and had (at least) one son.

(George) James Henry went to school at Eton, where he was regarded as a “scug”, and then, thanks mainly to President Warren’s positive memories of his Uncle Robert, got into Magdalen to study Modern History (1928–31), where he graduated with a 3rd after being tutored by the apostate theologian James Matthew Thompson (1878–1956) (see D.W.L. Jones) and the rising young medievalist Kenneth Bruce McFarlane (1903–66). A diffident and reclusive young man, James Henry did not enjoy his time at Oxford and made no mark upon either his College or the University. He later became a well-known architectural historian and conservationist who had a particular interest in country houses. Before the Second World War he worked for the Country Houses Committee of the National Trust and then served in the Irish Guards (1940–41). After the war he worked once more for the National Trust in several capacities and is credited with helping the Trust to acquire several hundred major listed buildings. In 1947, he published his first book, The Age of Adam (1947) and became a specialist on the Baroque. In 1934 he converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism, but later returned to high Anglicanism. His wife was the daughter of a General and the former wife of a zoologist (marriage dissolved 1950). She became a respected garden designer and co-edited several books on the subject. James Henry’s extraordinarily colourful life is narrated in careful and entertaining detail in Michael Bloch’s well-received biography, from which it is clear that he held his Uncle Robert in great respect. Thus, on 21 August 1982, the centenary of Bailey’s birth, he noted in his diary:

I remember my Uncle Robert with reverence and affection, for I was brought up to believe him to have been the gentlest, most saintly scholar and sportsman, the ideal of a pre-1914 English gentleman, adored by his colleagues among the House of Commons clerks, by his friends, by his two sisters, my Mama and Aunt Doreen, and by the working men at whose clubs he taught. I have one memory of him, like a muzzy, rapid shot of an old cinematograph film, chasing me around the yard at Wickhamford. This must have been during his last leave in the First War. He was wearing a black and white check suit and stiff collar, with his short hair parted at the side and a smooth, youthful, not quite handsome face. He was in his mid-thirties. As a boy I rejoiced when told I resembled him. I feel more in accord with him than with any of my relations.

An etching by the artist and architect John Buckler (1770–1851), entitled South-East View of Magdalen Tower (1805), which had hung in Robert Bailey’s room during his time at Magdalen, also hung in that of his nephew three decades later. It now belongs to the College.

(George) James Henry Lees-Milne

Richard Crompton Lees-Milne, who had managed the family’s cotton mill in Oldham for 25 years until it closed in 1970, retired to Cyprus in the same year, became caught up in the troubles there in 1974, and died on the island, possibly of an illness that he had developed due to cotton dust.

William John (“Bill”) Cuninghame (later Major), “a heavy-drinking Ayrshire laird” who had squandered his fortune over a dispute, had served during the Second South African War (1900–02) in a mounted infantry regiment which fought in the Transvaal and the Orange Free State (February–May 1900) and the Orange River Colony (May–29 November 1900 and 30 November 1900–1901). He was awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal (three clasps) and the King’s South Africa Medal (two clasps). During World War One he served with the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry (South Nottinghamshire Hussars), and at some time in his life he served with the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. He and Margaret Doreen lived at Ewen House, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, but after his death she moved to Foss Wold, Stow-on-the-Wold, Gloucestershire.

Education and professional life

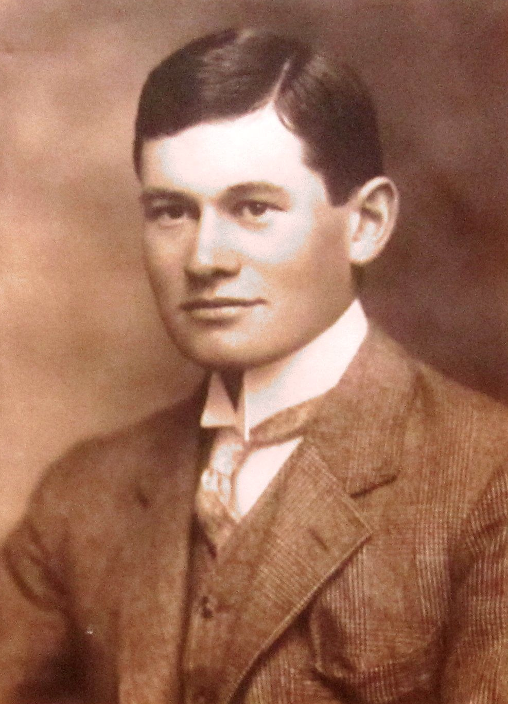

Robert Neale Menteth Bailey

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

He hated soldiering (though no-one would have guessed it, for he was always cheerful) but did his duty nobly, keeping all the while his soul fresh and beautiful, amid the horrors of war, like an oasis in the desert.”

As Robert’s parents died when he was a boy, he and his two sisters were brought up by rich relatives in Scotland and Wales. But while his sisters were educated by governesses and then attended finishing schools in Paris and Heidelberg, Bailey was sent as a boarder to Cheam Preparatory School, near Epsom, Surrey, from c.1889 to 1896 (cf. J.R. Platt, G.T.L. Ellwood, A.G. Kirby, L.S. Platt, A.F.C. Maclachlan, E.W. Benison, C.P. Rowley). Founded in c.1645 by the Reverend George Aldrich (1574–1658), it moved to nearby Tabor House in 1719, where it stayed until 1934 when it moved to its present site at Headley, Hampshire. It was sometimes known as Manor House Preparatory School because that, according to the Censuses, was the proper name of its buildings, and sometimes, from 1856, as Mr R.S. Tabor’s Preparatory School, when the Reverend Robert Stammers Tabor (1819–1900) became its Headmaster (until 1890) and set about turning it into a purely preparatory school and, arguably, the top preparatory school in the country.

In 1896, he was awarded a Scholarship to Eton College, which he held from 1897 to 1901. According to his Eton obituarist, he was “never widely-known”, probably because “his tastes were always scholarly”. Even so, he became the best friend of his fellow Scholar, School Captain and twice winner of the prestigious Newcastle Prize, William George Gresham Leveson-Gower (b. 1883 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, d. 1918), who was killed in action by a shell on 9 October 1918 at Awoingt, about two miles east-south-east of Cambrai, while serving as a Lieutenant with the 1st Battalion, the Coldstream Guards (cf. E.P.A. Moore) (and was buried in Awoingt British Cemetery, Grave III.H.1). Bailey also served in the Eton College Rifle Volunteers and was elected to a Demyship (Scholarship) at Magdalen in December 1900. He matriculated there on 14 October 1901, having been exempted from Responsions. He took the First Public Examination in Trinity Term 1902 and was awarded a 1st in Classical Moderations in Hilary Term 1903. In Trinity Term 1905 he was awarded a 2nd in Literae Humaniores (Hons) and he took his BA on 21 October 1905 (MA 1909).

William George Gresham Leveson-Gower (c.1902); detail from a group photograph of the Twenty Club

(Photo courtesy of Christ Church, Oxford)

The Twenty Club was a dining and debating society. It was founded in December 1886 as the Eclectic Debating Club and changed its name to the Twenty Club on 28 April 1887. It seems to have been one of those rare Oxford beasts: a dining club that actually did hold debates, and it was still going at least into the 1950s.

Bailey decided to apply for the Civil Service, and in late October/early November 1905, while waiting for the results of the qualifying examination, he travelled to Cairo, from where he wrote of his hopes and intentions to Leveson-Gower, who wanted to go down the same professional route and whose personality, extensive experience of living abroad, examination results, and multiple aristocratic connections would enable him, in 1907, to be accepted somewhat higher up the ladder as a Clerk in the Journal Office of the House of Lords. Leveson-Gower was then called to the Bar (Inner Temple) in 1911 and later allowed to transfer to the Diplomatic Service. Bailey wrote:

Being low on the Civil Service list, I shall be offered some bad Home Civil office, like the Post Office or the Estate-duty, and shall not easily get transferred. If I find myself vegetating at slavish work, I shall like to throw it up and look for something more romantic in the Near East. […] As it is, I have wasted my time in rather fruitless book-work, and it is rather too late to become worldly-wise.

But until he took up the post of Clerk in the House of Commons Committee Office in early April 1906, a job which, according to an obituarist, “left him freedom to read and wander during many months of the year”, he was able to indulge his romantic Wanderlust on an extended journey to the Middle East. From December 1905 he spent three months in the Levant, travelling to Aswan (6 December 1905), then back to Cairo (10–at least 19 December 1905), then to the northern Sinai Desert between El Qantara (Kantara) and El Arish (27 December), then northwards to Jerusalem (4 January 1906), Baalbec (19 January 1906), Damascus (20 January) and Constantinople (25 February). Eleven years later, as an officer in the Allied army that was following substantially the same route into Palestine, he would remember this journey with some irony. He had less time for such journeys in subsequent years, but in autumn 1906 he seems to have travelled in the Balkans, though all we know of that journey is that on 10 September he was in Cetinje, the Presidential seat of Montenegro, and that he came back to Britain via Weimar and Jena. Probably as a result of his stay in the Balkans, he had to spend January–March 1907 in the London Fever Hospital at Islington. And on 30 September 1907 he was in Amsterdam.

While at Magdalen, Bailey became a particularly close friend of his exact Magdalen contemporary G.M.R. Turbutt, and in August 1908, while en route to the family home in Scotland, he stayed with Turbutt’s family at Ogston Hall, Derbyshire. On 23 December 1912 Bailey wrote a letter to Leveson-Gower that was somewhat surprising, given that he was clearly a sensitive and introverted young man who would be put on bromide from 1913 to 1914 for the sake of his nerves. In it, he admitted that he enjoyed hunting – in contrast to the politics that formed the backcloth of his working life: “politicians I detest, and politicians pretending to judge scientists – out, hyperbolical knaves”. Two weeks later, on 5 January 1913, while suffering from one of the fits of self-doubt that afflicted him from time to time, he wrote another letter to Leveson-Gower, this time in a more confessional mode, in which he said that he had no clear sense of where he was going or what, despite his job in the Civil Service, he wanted to do with his life and commented, somewhat desperately: “I’m too ridiculous already to care a damn ab[ou]t being a little more so.” So perhaps Bailey was trying to remedy his indecisiveness and lack of a clear sense of direction and trying to prevent himself from “growing soft in a sheltered life” when, in September 1913, he found himself working his way across Canada in a fairly unplanned way by doing manual work on farms during the harvest season – an experience which, an obituarist later claimed, “proved good training for the war which so soon followed”. In July 1914, Bailey visited the university town of Jena, where he enjoyed the services of a tutor – presumably to improve his knowledge of German – and returned home via Cologne and Antwerp.

It was probably in about 1910 or 1911 that Bailey decided to give more direction to his life by becoming involved in adult education. Like his friend Leveson-Gower, he seems to have begun this kind of work by teaching part-time for the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA), which was founded in 1903 by Albert Mansbridge (1876–1952) and his wife Frances (c.1876–1958) as An Association to promote the Higher Education of Working Men (WEA from 1905). He was teaching especially in the Somers Town area of London, i.e. the notorious slum area behind Kings Cross and St Pancras stations, where Magdalen’s Mission would be situated at 1, Oakley Square (see C.I.S. Hood). An obituary in The Highway, the WEA’s monthly journal, by someone who had worked there with Bailey, paid him the following tribute:

Notwithstanding the heavy calls this made on his spare time, as a member of London’s WEA, he took an active part in the formation of our St. Pancras branch. His belief in education as a means of pleasure to the individual and as a factor in progress towards social improvement was no mere sentiment, but a faith worthy of constant effort and sacrifice. One incident comes vividly to mind: A lecture had been arranged, and Robert Bailey was very anxious to secure the attendance of some of the men from the poorest parts of the district; experience had shown that ordinary recruiting did not attract them, so he and another spent many hours in house-to-house visiting and distributing bills in public houses!

The obituary concluded: “Robert Bailey was a scholar and a gentleman; it is hard to realise that he is no more, but the memory of his charming personality, his cheery smile, and his unbounded enthusiasm remains with us as an inspiration.”

Round about the same time, Bailey also began to work with equal enthusiasm and commitment as a part-time Classics lecturer at the Working Men’s College, also in the area behind King’s Cross in Crowndale Rd, London NW1 (originally the London Borough of St Pancras, now the Borough of Camden), that had been founded in 1854 by a group of Christian Socialists whose leading light was the radical and highly controversial theologian F.D. Maurice (1805–72). John Harrison’s centennial history of the College mentions Bailey twice, once in a context that relates directly to his evangelism on behalf of the WEA. It records how, in October 1912, Bailey spoke up at a meeting of the Old Students’ Club when it was discussing the long-standing problem of how to remedy the declining percentage of manual labourers among its students (from 53% in 1893–94, to 43% in 1901–02, to 38% in 1910–11). Bailey, Harrison wrote, who was “one of the keenest of the younger teachers”, opened the discussion by drawing attention to the problem, and contrasted it “with the success of the W.E.A. and the tutorial classes in attracting them. ‘How are we to get them?’ he asked; ‘In my opinion, we must go out to them, cease to be self-contained, and open ourselves out among them.’” Harrison continues:

Various specific suggestions were made at the meeting, and there was a general feeling expressed that the College should get into closer touch with working men’s organizations [e.g. Co-operative Societies, Working Men’s Clubs and Dockers’ Institutes]. This opinion was duly passed on to Council, which in the following February resolved “that, with a view to attracting a greater number of manual workers to the College, attempts should be made to induce representative labour leaders to give lectures at the College”.

Furthermore, in May 1913 the composition of the Council was revised to the above end, to make its composition “more democratic and in closer contact with working-class bodies”. So it is perhaps not surprising that a second obituary, which appeared in the Working Man’s College Journal in December 1917, was equally generous with its praise for Bailey, describing his death as “one of the greatest losses the College has suffered through the war” and adding that:

Robert Bailey stood almost by himself in the College as a character [who was] entirely loved by everyone who knew him: he was the very essence of greatness, self-effacement, and self-denial. He was a spirit so rarely gentle and kindly that the feelings of all who came to know him turned to love and friendship for him. The love of man is inspired in the College as it is in no other place that we know. It is a gift from our Founders. Robert Bailey was one of the rarest and best of the men who followed in their footsteps, and he possessed in a singular degree the gift of loving and inspiring love. How we shall mourn his loss!

Then, at the College’s monthly Council meeting that was held on 20 February 1918, Arthur Sinclair Lupton (1877–1949), a Civil Servant, Classicist, and member of a prominent family of educationalists, paid yet another fulsome tribute to Bailey’s work for the College when he moved the following resolution: “The Council wish to record with great sorrow the loss which the College has suffered by the death of Mr. Robert Bailey. He died, as he lived, seeking out and following up his duty with no regard to himself, and he has left behind him in the College which he loved a memory of gratitude and deep affection.” Lupton then went on to speak of his own personal affection for Bailey: “Among all the fine men we [have] lost in the war, we should feel for none more than we felt for him. No-one [has] done more to continue and strengthen the College spirit.” He concluded this part of the meeting by stressing that “no-one who came across Bailey in the College could fail to feel more than a liking for him. He just won our hearts, and it was a pleasure to see him always. He had ways, which came from the heart, of doing and saying the right thing, and we were the better for having known him.”

Bailey was a member of the Cavendish Club, 119, Piccadilly, London W. By 5 December 1906 he was living at 4, Waverton Street, London W, and he was still there in 1908. At the time of the 1911 Census he was staying with his aunt Margaret Doreen Cuninghame at her home at Ewen House, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, but by January 1913 he had moved to 67, Camden Street, Middlesex, London NW, presumably to be nearer his work in adult education.

Military and war service

Bailey was 5 foot 11 inches tall and in a letter of 4 September 1915 to Leveson-Gower, he mentions having joined the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps (“The Devil’s Own”) in about 1906 – though some of his later letters suggest that he was not a very active member of that unit. Leveson-Gower, in contrast, had joined the same unit as an officer in 1907, taken to army life very easily, and during the war would become a General Staff Officer (Grade 3) (Captain) and then, in order to get to the front, a Lieutenant in the Coldstream Guards.

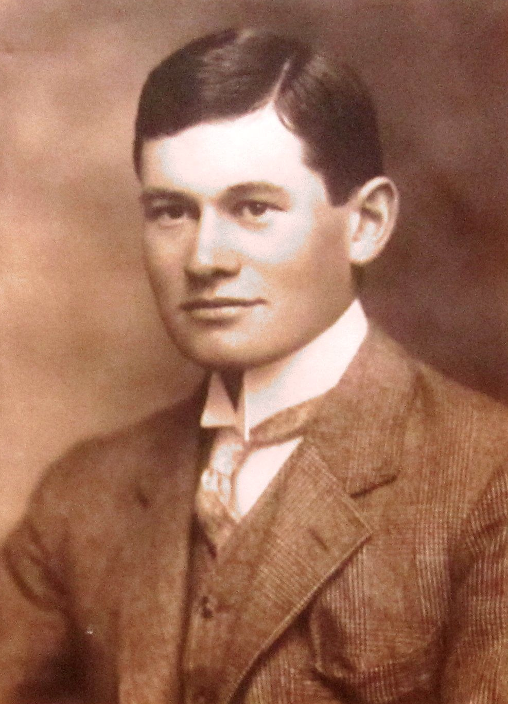

William George Gresham Leveson-Gower (c.1917)

(Photo courtesy of Christ Church, Oxford)

Bailey’s letters from the Palestine front suggest, perhaps with excessive modesty, that he was not a very experienced horseman. But he did enjoy riding to hounds and that plus the imminence of war seems to have re-awakened such martial spirit as he possessed and caused him to become active again in his old unit, this time from August to September 1914 as a Corporal in its Mounted Squadron. But on 8 September 1914 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the East Riding of Yorkshire Yeomanry (Territorial Force), which had been founded on 4 August 1914 at Railway Street, Beverley, Yorkshire, as part of the Yorkshire Mounted Brigade, and assigned to ‘H’ Squadron.

By 7 October 1914 the Regiment was at the small market town of Pocklington, 18 miles east of York, and it was still there on 31 October 1914. On that day, Bailey wrote a very interesting letter to his family in which he wrote of his “hatred of machinery in any form”. But he also suggested that army life was starting to make him feel very lonely and out of touch, since the letter continues: “The only news one gets of anybody now is by reading the [London] [G]azette. […] That and the casualty list, but as far as I am concerned[,] that has about done its worst, now that Turbutt is dead.” Bailey’s juxtaposition of his dislike of machinery and close friendship with G.M.R. Turbutt is no accident, since both of them were temperamentally conservative; neither was greatly interested in the typically manly pursuits of the day, though both did a little hunting, shooting and fishing now and again; both were happier in the rural past than the urban present; and both had a love of things antiquarian. Immediately after his friend’s death at Poelcappelle on 21 October 1914, Bailey wrote the following terse, but deeply affected letter to Turbutt’s mother, to whom he was particularly attached, having no mother of his own: “Dear Mrs Turbutt, I cannot say anything, any more than if he was my brother. Some day I shall write. Today I can’t write. I am[,] Yours very sincerely[,] Robert Bailey.”

In mid-November 1914 the Regiment moved to Seaham Hall, Seaham Harbour, in Co. Durham (now a luxury spa hotel), and on 3 December 1914 Bailey described his military experiences there in a long letter to William Leveson-Gower:

Physical drill on horses […] is a pleasant item: changing horses, doing exercises, & wrestling, sections against sections. It is a very comfortable house of Lord Londonderry’s [the 5th Marquess], & the men are billeted in large dismantled drawing rooms. We are uncommonly well mounted and fairly well equipped, and we don’t overwork ourselves.

But unusually for Bailey, he also started to talk about the effect that the war was having on his thoughtful but fairly conventional religious convictions:

I wish I could win any victory by prayer and fasting. The more I need it[,] the less prayerful I am. Possibly if I prayed & fasted a bit I might begin to think of somebody else instead of my silly self [–] which has been my entire absorption for 2 months wondering how I shall ever get into soldiering, or what congenial form of it is discoverable – That, and the fact that one isn’t using one’s wits at all (at least I am not) but merely floundering through a routine among half-tolerant strangers, make one quite unable to concentrate on any form of thought.

Then, belatedly, and in a postscript, Bailey began to dwell on the recent deaths of several of his friends:

It is sad to see some of our August men already falling, like Waghorn & Powell [almost certainly Leonard Pengelly Waghorn (1891–1914), killed in action at Ypres on 6 November 1914, aged 23, while serving as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, the Royal Berkshire Regiment, no known grave; and Harold Osborne Powell (1888–1914), killed in action at Ypres on 31 October 1914, aged 26, while serving as a Second Lieutenant in the 4th Dragoon Guards (Royal Irish), no known grave]. The wickedest part is losing men who are so much more than soldiers, who have so much more to live for. A soldier’s death can’t be the crown of their life. Or shall we say their sacrifice is perhaps the more inspiring? The Athenians were something like them, citizens first, and soldiers a long way second, and Pericles could never have said those things about professional soldiers[.] – Perhaps we shall come to think of them in the light of the funeral speech, but what a wanton waste it seems now. With Turbutt & Alfred Schuster gone [Alfred Felix Schuster (1883–1914), killed in action at Ypres on 20 November 1914, aged 31, while serving as a Lieutenant in the 4th (Queen’s Own) Hussars, no known grave] I have no special friends at the front, unless Merriman of the Inland Revenue is there [probably William Robert Merriman (1882–1916), killed in action on the Somme on 15 August 1916, aged 34, while serving as a Second Lieutenant with the 8th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade, no known grave].

On 30 May 1915, when his Regiment had just been reassigned to the 1/1st (North Midland) Mounted Brigade, part of the 1st Mounted Division, Bailey wrote a long letter to Turbutt’s mother from the Crescent Hotel in the seaside town of Filey, Yorkshire, describing his recent military experiences:

We came here on Wednesday, after 5 days trek through glorious country in glorious weather. From the bleak North Durham pit country we gradual[ly] got into woods and well farmed country, then into the Cleveland hills from Stokesley to Helmsley, then to Pickering, then here. As we got into Yorkshire the men began to notice differences. In almost every village somebody seemed to recognise somebody who had once been in his own neighbourhood. Even a stallion of Lord Middleton’s was recognised and appraised 30 miles from home. But the thing that delighted my troop more than anything was when a village school turned out to cheer us. “There’s Yorkshire for you” – “feels like home somehow” – After riding and walking over desperate hills nearly all day to Helmsley[,] we were turned out at midnight to march 6 miles and surprise the reserve Scots Greys, who were out against us. We attacked at 4.30 and fairly caught them just saddling up their horses to come and raid us. The night was as magnificent as the day, and all through fields and tracks with a local guide. It was the kind of week that only comes about once a year, and I don’t remember a week in May to equal it since 1905, our last summer at Magdalen. Wednesday was nearly tragic. This time it was another [Y]eomanry, who were waylaying us on the way to Filey. Our [S]quadron were made to charge down a narrow macadam road into a village, with men firing blank rounds behind the wall on each side. Twelve men and horses tumbled over one another in a heap, but only two men were seriously hurt. It was rather overdoing the image of war, though. It was a pleasant week, and the men enjoyed being feasted by their hosts. “We had our boots cleaned for us”. “Oh but we had tea and a spread before early stables”. Another party of ten had a musical accompaniment to breakfast at 6 a.m., the daughter of the house playing the piano. You can guess how these things count for men who have been crowded together for 8 months, living on the eternal dicksey [dixie ??]. Here at Filey the men are in boarding houses, but the horses are in the open, getting rained on in a muddy field. It is rumoured that we are to join the North Midland Mounted [B]rigade on Salisbury Plain next week. But we pay no attention to rumours now. Every morning on the march my troop sang like starlings, after being mute all winter. There are big sands here, when the tide is out, big enough to drill the [R]egiment together. […] I don’t complain of being kept at home, I complain of being a most unmilitary subaltern, with no early prospect of being discharged & allowed to enlist. But that is only complaining about myself. I don’t want to go to the front for its own sake, but only so as to get a stage nearer the end of this parade life.

By mid-June 1915 the Regiment was in Diss, south Norfolk, and by 21 June 1915 it had moved to Riddlesworth Hall, about half-way between Diss and Thetford.

By 4 September 1915, the Regiment had moved to Costessey Park, just west of Norwich, Norfolk, where it re-trained as infantry for three weeks until, on about 3 October 1915, it was given back its horses. It carried on training here until 26 October 1915, when it left Costessey, travelled by train to Southampton, and embarked on the following day in the RMS Victorian (1904; broken up in 1929) for the Salonika front. But plans changed while the Regiment was at sea, and on 10 November 1915 the Regiment disembarked at Alexandria, Egypt, from where it marched to the ironically named Châtelet-les-Bains Camp – so-called, probably, because the living conditions there, in the desert, were the exact opposite of those of the original, near the fashionable spa town of Thonon-les-Bains on the south side of Lake Léman amid the French Alps. The Regiment trained and acclimatized itself here until 22 November, so that, like the other units of the North Midland Mounted Brigade, it could become part of the hastily created Western Frontier Force (WFF) (cf. H.F. Yeatman). Commanded by Major-General Alexander Wallace (1858–1922), the WFF was formally created on 11 December 1915 to deal with the invasion eastwards by Turkish-backed Senussi tribesmen along the north-western coast of Egypt from Es Sollum.

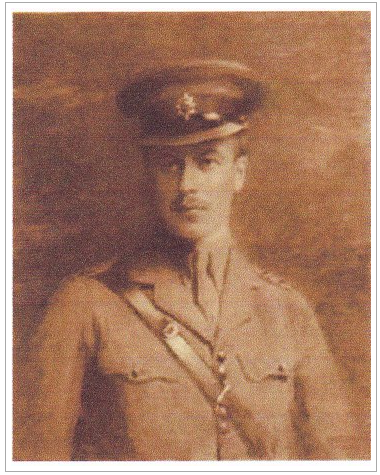

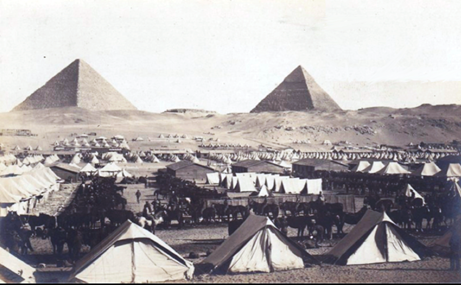

The huge Allied Camp at Mena (near the Pyramids at Gizeh)

The huge Allied Camp at Mena (near the Pyramids at Gizeh)

On 28 November the Regiment entrained for Mena House Camp, a well-known hotel and resort that overlooks the pyramids near Cairo, and was taken to the oasis town of El-Fayoum, c.75 miles south-west of Cairo, just west of the Nile, and near the eastern edge of the Fayoum Depression. From here it marched to nearby Deir-el-Azab Camp, where it carried on training until 19 December as part of the WFF and it then marched further south-westwards, into the desert, to the village of Abu Gandir, where it trained until 10 January before returning to Deir-el-Azab.

The Camp at Kasr el Gebali (January 1916; BAI/5)

(Photo courtesy of the Parliamentary Archives, Westminster)

The Regiment stayed here until 24 February, when it was sent south-west into the desert once more, this time to Sabwani Abu Galil, in the south-west part of the El-Gharaq Basin, in order to counter a feared Turkish-led Senussi advance eastwards towards the Nile from the huge Bahariya Oasis, several hundred miles due west of the town of Minia on the Nile. This did not materialize immediately, and until mid-March 1916, the Senussi uprising was largely confined to the coastal stretch of northern Egypt and did not follow the line of oases that ran east-south-eastwards across the Western Desert from the Libyan frontier. So Bailey, like so many of the men of the WFF throughout 1916, was beginning to find life in the desert physically unpleasant and the task of being long-stop in the middle of the Libyan Desert very boring, and on 6 March he wrote to his sister Helen Christina:

I have found about a square yard of shade up against our mess tent, and there is just enough breeze to make it more tolerable than inside. The bell tents, with no inside lining, simply act as ovens. […] The flies stop one sleeping in the afternoon, when it is too hot to do anything but sleep. […] Each troop takes it in turn to patrol the desert, which is the most enlivening thing we do here. […] The most comforting reading just now is the Psalms. The people who wrote Psalms always seem to have been bullied by somebody, as we are, and to have taken it desperately seriously, as we do. But they always end up with a comforting maxim like “Tarry thou the Lord’s leisure” [Psalm 27:16] or “The just shall inherit the earth” [Psalm 37:9] or “In due time we shall reap if we faint not” [Galatians 6:7], we shall reap if we don’t shoot ourselves.

On 8 March 1916 the Regiment returned to Abu Gandir and on 13 March its War Diary recorded that “2/Lt Bailey and 2 ORs [other ranks] proceeded on long[-]distance patrol with detachment Bikaner Camel Corps” – presumably to scout the empty Fayoum Depression well to the south-west of El-Fayoum and/or the most extreme edge of the possible invasion route along the north coast of Egypt. Either way, the task was very uninspiring, not least because it meant being out of range of postal services for three weeks and because the Senussi threat had dwindled by mid-April 1916. So on 10 April, having got back from the deep desert, Bailey wrote to Helen that “We are all sick of the desert” and the Regiment stayed more or less where it was until 9 May, training in musketry and outpost duties in order to have something to do. On 2 May Bailey was promoted Temporary Lieutenant (confirmed 1 June) and on 7 May he wrote to Helen that on the previous day he had been out fox-hunting with some brother officers, adding: “Much as I detest horses, I think we would all be unhappier without them. Each man can make a pet of his horse, in a way, though he gives it more curses than caresses. Failing horses, we would have to keep beetles and lizards and poisonous spiders.” On 31 March 1916, i.e. during this period in the deep desert, the 1/1st North Midland Mounted Brigade was redesignated as the 22nd Mounted Brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General Frederic Arthur Bashford Fryer (1871–1943), and on 9 May it proceeded even further south-westwards into the desert, to Kom Medina Madi, in the south-west of the Fayoum Depression. Here it camped on the aptly named Ruined Hill, just to the east of the town, where a major archaeological dig had, during the pre-war years, begun to unearth a Middle Kingdom site that dated back c.3,600 years and included a very fine temple dedicated to the cobra-goddess Renenat.

Bailey’s Regiment, whose effective strength was now 18 officers and 394 other ranks (ORs), stayed at Kom Medina Madi for three months and suffered intensely from the intense heat, the light and the sand. On 16 May Bailey wrote to his sister Helen: “In the afternoon it is something over 120° [49°C] in any tent, and the breeze is from the south & hot – One’s eyes being the most sensitive part, one wears goggles to keep the breeze off them”, and in early June he was given some leave in Cairo, which he described in a letter of 10 June as “divine”. But his sense of general futility did not ameliorate, for on 9 July he wrote to his Helen that the latest news “points to our being permanently marooned – maddening. O that I knew the army better & could get somewhere to be doing something. What an imperial mug I was not to enlist [on] 4th Aug[ust].” So fearing a lengthy stay, Bailey informed her on 16 July that he had had a stone hut built recently at a cost of 3 guineas (= £3 3s.) “with a flat roof and a mud floor […] – 20′ x 10′ with 18″ walls – and a roof that actually keeps out the rain, being matting laid on beams and plastered with mud on top”. The dwelling was, he reported “deliciously cool in the afternoons”. On 24 July Bailey became Acting Adjutant for a week, and after returning to Deir-el-Azab Camp on 12 August 1916, his Regiment trained and guarded the “west front” of the Fayoum Oasis “from troublesome people who may float in from the desert. They don’t, but here we are.” By this time, Bailey was getting more and more fed up with army life, and on 9 September 1916 he wrote in a letter to his friend Leveson-Gower:

All but 2 or 3 of my old friends are gone, and I don’t seem able to make new ones now. […] I long for office work, for its variety, and for the feeling that at least one does something day by day, instead of dragging on in almost complete inertia. For 3 months we were too short of men to do anything but exercise, and had to keep under cover, except for watering and feeding, from 10.30 to 4.30. Really you don’t know what monotony is till you have come here or to a prisoners’ camp, which I imagine must be worse.

Two days later the Regiment set off southwards to Khargat Oasis, the southernmost of Egypt’s five oases in the Libyan Desert that is situated c.315 miles due south of El-Fayoum and c.65 miles due west of Luxor in the Nile Valley. The Camp here was known as “Leadbeater Camp”, presumably an ironic reference to Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854–1934), a Theosophist and very prolific author on mystagogic subjects, one of whose books was entitled The Perfume of Egypt and other Weird Stories (1911), and Bailey, for whatever reason, described the camp as “delightful”. His Regiment trained and did outpost duties here until 31 October, when it returned to Deir-el-Azab for a month of Squadron training. During this period, Bailey, who was an avid reader and who, according to an obituarist: “always […] carried with him Thackeray’s Greek Anthology, stripping off first the cover and the less precious pages, lest it should interfere with military necessities”, read H.G. Wells’s recently published novel Mr Britling Sees it Through (1916). This book had already touched a nerve with many people in Britain since it recounts the way in which an eccentric middle-class family reacts to the outbreak of war, copes with it when casualties occur, undergoes shifts of opinion during the two years 1914–16, and culminates in Wells’s plan for a post-war world government whose values are derived from a kind of Christianity. But unlike N.G. Chamberlain, whose political views leaned more to the left and who, six months earlier, had responded positively to the novel as a whole, Bailey enjoyed only its first half and discovered nothing in the “tedious” second half to counteract the boredom of military life. Indeed, the above obituarist would later say that “during all the weary months of waiting in Egypt he yearned for Eton, and asked last Christmas for photograph-cards of the river and the playing-fields to refresh his soul in the heat of the desert”.

But on 28 October 1916, by when, on his own admission, he was still not used to soldiering, Bailey was sent off to Cairo to do a three-week course on cavalry tactics, from which he returned to his Regiment in time to move to a new camp on 28 November 1916. Then, at some point in early December 1916, after a year of seemingly useless tedium in the WFF, the 22nd Cavalry Brigade began a long journey north-eastwards, towards the northern Sinai Desert east of the Suez Canal and the Palestine front, that was interspersed with periods of rest and training. It was probably during one of these, on 7 January 1917, before the Regiment had crossed the Suez Canal, that Bailey, in what he would describe retrospectively as a “selfish letter”, told his sister Helen about his little pleasures as a cavalryman and his future hopes:

The only public appearance I make, without feeling a fool, is when we have some jumps, and our chaps are such fools over jumps that even I can set them an example. Their one idea of jumping is to kick their horse on as fast as they can and crash through everything. Fancy me being told that I was one of two people who had my horse collected for its jumps, like I was this morning. It makes me feel young and lusty again. These wild lads don’t want to have the trouble of cleaning their saddles, so when we put up some jumps, like we did this morning, half of them turn up with a blanket and surcingle, on horses that haven’t jumped since October. I do think a horse deserves the best you can do for him, over jumps, and I hate to see these chaps hanging on anyhow, kicking their horses over.

In the same letter he wrote:

we live in hope of getting to the front some day. How I would love to be one of the first in Jerusalem, to make it a Christian city once and for all. Shall we be there for Easter? Do we even intend to push? We don’t know any more than you do. We never thought we would have pleasant recollections of the Fayoum, and now we have, within a month of leaving it.

Much to Bailey’s amusement, his Regiment continued its journey to the Palestine front along the same route that he had travelled independently during the winter of 1905/06: on the main road eastwards to El Arish via the major railhead of El Qantara (Kantara) (9 January 1917), the little oasis of Dueidar, ten miles west-south-west of Katia, where it did several weeks training, and Romani, four miles north of Katia (19 January), where a major victory had been won against the invading Ottomans on 23 April 1916. On 28 January 1917 Bailey, who was by now very tired indeed of army life, wrote to his sister that he loathed “every sort of responsibility […] and none so much as the job I have now”. On 31 January 1917 Bailey’s Regiment arrived at the desert town of Bir el-`Abd, 15 miles east-north-east of Katia and by this time a major station on the railway which the Allies had been building at the rate of a kilometre a day from El Qantara to El Arish, 90 miles to the east.

Laying the railway across the Sinai Desert (1916)

British soldiers filling their canteens with water near Romani (1916/17)

A camp in the Sinai Desert near the Village of Bir el-`Abd (1916/17)

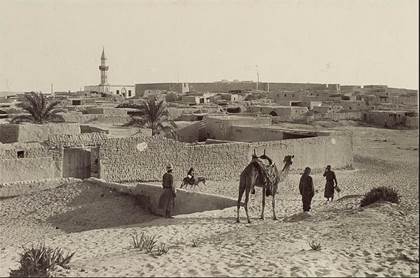

The walled town of El Arish (probably before 1916)

The railroad had reached El Arish as recently as 4 January 1917, progressed as far as Deir el Belah, not far up the coast, in mid-April, and extended a branch line out eastwards into the Sinai Desert as far as El Shellal, seven miles east of Rafah, allowing reinforcements, but also ammunition, food and most importantly water, to be brought to men and horses who were at the front across a wide area of desert. El Shellal, it should be stressed, was on the Wadi Ghazze, a deep river valley “of varying width – from 30 to 200 yards across, and with precipitous banks from 10 to 20 feet high” that runs through the desert from south-east to north-west. It is dry in April, but floods during the rainy season and issues into the sea about five miles south of Gaza, in 1917 Palestine’s second largest city.

The wooden railway bridge across the Wadi Ghazze, Shellal, Palestine (c.1917)

The north-eastern part of the Sinai Desert

Until 16 February 1917 Bailey’s Regiment trained and went out on exercises in the Sinai Desert, and on 3 February he wrote to his sister that they had had no cover for three nights: “We crouched behind a scrap of matting or a sheet of corrugated iron or a blanket propped up with swords, but I found the best protection was to put my blanket right over my head like a wedding veil, and have a short sharp walk when the rest of me got too cold to sleep.” Then, after advancing eastwards for a few days along the old caravan route, i.e. across rough ground that had seen fighting a few months previously, Bailey’s Regiment reached El Arish on 20 February. This important coastal town had been captured on 23 December 1916 by the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) Mounted Division under the command of the Australian Major-General (later Lieutenant-General Sir Henry) Harry Chauvel (1870–1951), and it was here that the 22nd Mounted Brigade, consisting of the Staffordshire Yeomanry, the Lincolnshire Yeomanry, and Bailey’s East Riding of Yorkshire Yeomanry, joined that Division and became part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), whose Deputy Commander overall and GOC (General Officer Commanding) in the northern Sinai Desert was the Canadian, Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Macpherson Dobell (1869–1954). The Division immediately continued its advance east-north-eastwards along the coast to the small town of Sheikh Zowaiid, c.23 miles from El Arish, and on its arrival on 23 February it was sent further to the east, out into the Sinai Desert on outpost duty, which occupied it until 10 March 1917. On that day, Bailey’s 22nd Mounted Brigade pushed on further along the coastal route to Bir el Melalha, a suburb of the frontier town of Rafah, between Egypt and the Gaza Strip in Palestine, which had been captured on 23 December 1916 by the Desert Column of the EEF (later the Desert Mounted Corps) under Lieutenant-General (later Field-Marshal) Sir Philip Chetwode (1869–1950), thus completing the recapture of the Sinai Desert from the Ottomans.

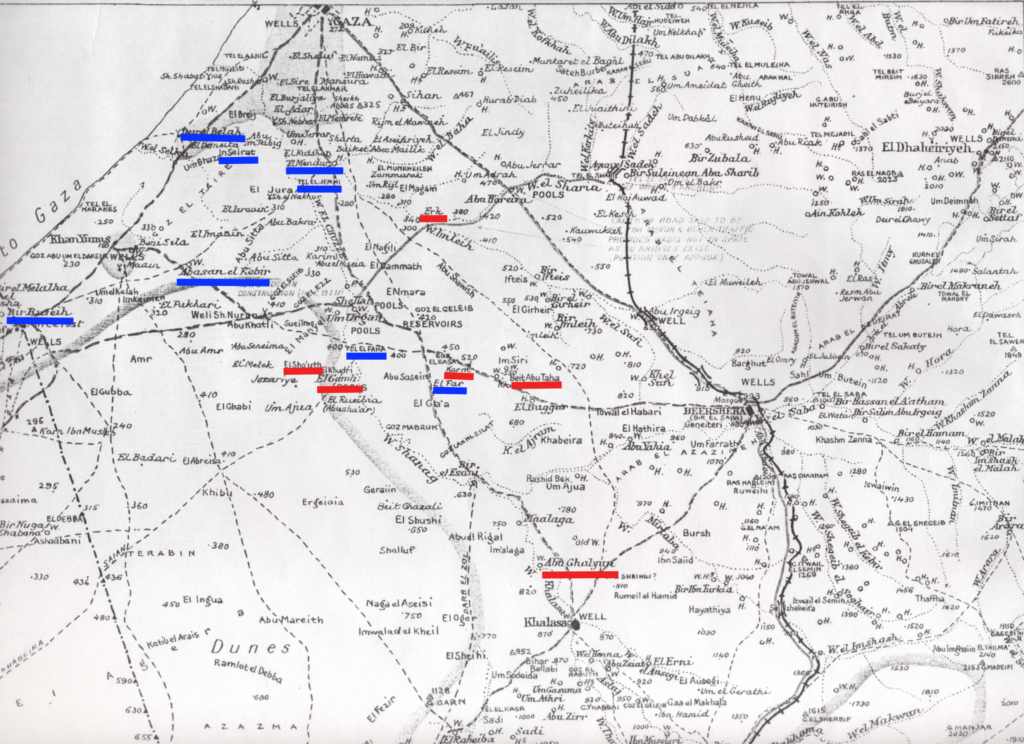

In the run-up to the First Battle of Gaza (26–28 March 1917), Bailey’s Regiment was mainly engaged in reconnaissance patrols, but on 25 March 1917 it proceeded to Deir el Belah, a coastal village in southern Palestine about halfway between Rafah and Gaza, but on and during the night of 25/26 March, elements of the ANZAC Mounted Division crossed the Wadi Ghazze and reached their allotted assembly positions. The Battle began at 02.30 hours on 26 March 1917, and at first the Allies made rapid progress, thanks in part to a thick sea fog, and had all but surrounded the city of Gaza by 10.30 hours without any serious opposition from the Turks. But lack of up-to-date information caused delays and over-cautious generals failed to seize opportunities for want of such intelligence. So by late afternoon, General Dobell decided to pull his troops back from Gaza if the city had not been taken by nightfall. Dobell suffered badly from the want of clear and reliable intelligence and so was unaware of significant localized Allied victories – e.g. the capture that afternoon, by infantry and Bailey’s 22nd Mounted Brigade – of the well-fortified Turkish positions at Ali Muntar, the high point less than a mile to the east of Gaza which dominated the town, and the strength of his troops’ local positions. More importantly still, he did not learn, until it was too late, of “an intercepted Turkish radio message” which “revealed that the Gaza garrison was on the point of collapse and would have rapidly surrendered under the pressure of further attack”. Moreover, as Dobell also feared that the Allied troops who were encircling Gaza would be outflanked by Turkish reinforcements from Huj to the north-east and Beersheba to the east and south-east, he issued orders at dusk on 26 March for the Allied Divisions to withdraw. The withdrawal began in earnest at 19.00 hours on 26 March and was complete by dawn the following day. Whereupon a large Turkish force counter-attacked just south of Gaza and pushed the Allies back still further, after they had suffered somewhere between 2,400 and 4,000 casualties killed, wounded and missing during the fighting.

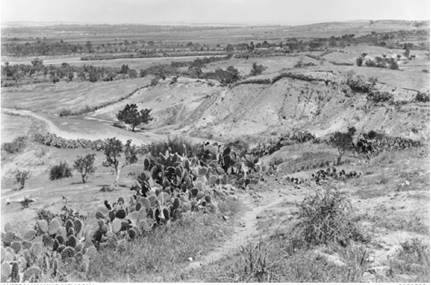

The hill of Ali Muntar, photo taken eastwards from the town of Gaza

View of Gaza from the hill of Ali Muntar; the coastline can be seen in the background. One of the cactus hedges which caused the attacking Allied troops great difficulty can be clearly seen to the left of the track in the foreground.

Unfortunately, the War Diary of Bailey’s Regiment has little to say either about the above events or its participation in the Second Battle of Gaza (17–19 April 1917). But during the gap of three weeks that separated the two Battles of Gaza, the Allies extended the new railway to Deir el Belah on the coast below Gaza, and used it to bring up eight Mk 1 tanks, 14 pieces of heavy artillery, and the two remaining Brigades of 74th Division (see F.R. Charlesworth). On the other side, the Turks had reinforced their defensive positions in and around the city, widened and deepened the front-line trenches and defences, and extended their line of entrenched positions and redoubts 12 miles east of Gaza to Abu Hureira and c.18 miles south-east of Gaza towards Beersheba. General Dobell knew of the military significance of these changes and decided that his second assault on Gaza would be more like those being conducted on the Western Front in Europe. Three Infantry Divisions – the 52nd, 53rd and 54th – would make a frontal attack on the southern side of the city and this would be preceded by a heavy and systematic bombardment of the enemy positions that would include the use of eight tanks and c.350 gas shells as well as heavy-calibre shells from ships off-shore.

So on 17 April Dobell got his infantry into position and the bombardment began at 05.30 hours on 19 April. But the latter, even with the gas shells, was weak and ineffectual; the tanks proved “a disappointment”; and the infantry made little progress against the Turks’ excellent defensive positions. Nor, on the battle’s opening day, did Dobell make much use of his Mounted Divisions even though the terrain was more favourable in the hot dry weather, since, as on the Western Front, it was assumed that they would rely on the infantry to create gaps through which they would charge – and the gaps did not materialize. Then, once the fighting began in earnest on the Battle’s second day, Dobell used his cavalry “wide on the right” – as a screen in the desert to the east, north-east and south-east in order to protect the right flank of the Allied infantry against Turkish reinforcements and flanking attacks during their efforts to break through the Turkish trenches. So even though the events of 17 April made immediate use of the ANZAC Mounted Division, their role was a static one, and Bailey’s 22nd Mounted Brigade was not involved until the following day, when it was left holding a defensive outpost line on its own while the rest of the Division went back to the new railhead at El Shellal, on the Wadi Ghazze, in order to water. During this interlude the 22nd Mounted Brigade was frequently bombed by enemy aircraft and suffered casualties, but as the ANZAC Mounted Division’s total casualties amounted to 102 men killed, wounded and missing, the 22nd Mounted Brigade’s loss rate cannot have been excessively high. Nevertheless, the Second Battle of Gaza proved to be an even worse defeat than its immediate predecessor, and when it ended on the evening of 19 April, Gaza had not been taken, mainly because the attacking infantry had not had adequate artillery support, and the Allied casualties had amounted to c.6,400 men killed, wounded and missing, hundreds of whom were still lying where they had fallen – in long lines in front of the Turkish trenches – when the Third Battle of Gaza began in November.

Allied soldiers burying the bodies of the dead after the Third Battle of Gaza in November 1917, but also the bodies of the dead that had been left in the open since the Second Battle of Gaza in April 1917. Those nearest the camera were probably some of these since their bodies appear to have been mummified.

So as a result of his two defeats at Gaza, General Dobell was relieved of his command on 19 April 1917 and returned to England. He was then replaced on 21 April 1917 by Lieutenant-General (later Field Marshal, 1st Baron Chetwode of Oakley) Philip Walhouse Chetwode (1869–1950); and the Australian, Major-General (later General) Harry Chauvel (1870–1951), took over command of Chetwode’s Desert Column (later the Desert Mounted Corps). Finally, on 28/29 June 1917, General Murray himself was recalled to Britain and replaced by the more dynamic – and more accessible – Lieutenant-General (later Field-Marshal) Sir Edmund Allenby (1861–1936), whom Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, had ordered to capture Jerusalem before Christmas “as a Christmas present for the people of Great Britain” and who immediately set about reorganizing the Allied forces in Egypt in preparation for an autumn offensive.

Before his dismissal, General Dobell had considered resuming the attack on 20 April 1917, but when he heard of the losses, he postponed the continuation for another day and then ordered his troops to dig in where they were. By this time, however, the 22nd Mounted Brigade had been sent back southwards to Tel el Fara, a hill with precipitous sides that rose abruptly from the plain on the eastern bank of the Wadi Ghazze and was located just a mile-and-a-half south of El Shellal. After staying there for two days, the Brigade moved through the desert in a long loop that began at El Nagili, five miles north of El Shellal, continued to the outpost line near El Mendur, seven miles due south of Gaza City, then returned on itself to Tel el Fara via Abu Sitta (24 April), five miles north-west of El Shellal. Bailey’s Regiment stayed here until 1 June, doing outpost duty, digging trenches and going on reconnaissance patrols. Bailey said something about this inactivity in his letters home, writing with great relief on 18 May that his Brigade had been pulled back from the trenches and that, on the previous night, he had slept with his breeches off for the third time in nearly five weeks and the first time for three weeks. But he then concluded, in a tone of ironic irritation, that his unit was about to be sent “on some quite obscure, inglorious and utterly safe errand for about a fortnight”.

After the second débâcle at Gaza, a stalemate set in along the line from Gaza to Beersheba that lasted for six-and-a-half months, not least because the desert heat, which at that time of the year rose as high as 115ºF (46ºC), inhibited almost all military activity, and on 3 June 1917 Bailey informed his family in England that although he had not had a day’s leave since leaving Fayoum at the beginning of December 1916, his Regiment was now enjoying a “seaside holiday” – at Tel el Maraqeb, as its War Diary confirms, five miles west of Wadi Ghazze and a recognized recreational centre for troops, especially ANZACs. But he then continued with some irony that although “it is divine to be on the shore, bronze all day, no dust, French cookery and a double change of raiment”, the spell by the sea was by no means all holiday: “There is such a glare and such a complete absence of shadow that you often can’t make out dips and rises unless they are on the skyline.” With more time to reflect, he also remarked, resignedly, that the war was “going on for so long that we may as well put our lives on a permanent footing to suit it, and not think about peace”. And the relaxation of leave, he implied, raised the perennial problem of boredom, since with so little to do, the men had organized “a prize fight between a big spider & a scorpion” that had been “attended by the General & Brigade Staff”.

Bailey’s Regiment resting on the beach, probably in early June 1917 at Tel el Maraqeb, where there are steep cliffs just behind the narrow beach; BAI/5)

(Photo courtesy of the Parliamentary Archives, Westminster)

On 8 June 1917, Bailey’s Regiment left Tel el Maraqeb for the village of El Fuqhari, four miles east of Rafah, where it stayed for six weeks, enabling Bailey to go to Cairo in late June for three days of dental work. Then, between 20 June and 22 July 1917, as part of General Allenby’s reorganization of his command in the northern Sinai Desert, two existing Mounted Divisions, each comprising four Brigades (the ANZAC Mounted Division and the Imperial Mounted Division), were turned into three Divisions, each comprising three Brigades. One of these new Divisions, commanded by General George de Symons Barrow (1864–1959), was designated the Yeomanry Mounted Division and formed on 20 June 1917 at Khan Yunis, three miles north of Rafah on the coast, from Yeatman’s 6th Mounted Brigade (which transferred out of the Imperial Mounted Division and joined the new Division at el Maraqeb on 27 June 1917), the 8th Mounted Brigade (which arrived in Egypt from Salonika on 8 June 1917 and joined the new Division at El Fuqhari on 21 July 1917), and Bailey’s 22nd Mounted Brigade (which transferred out of the ANZAC Mounted Division and joined the new Division at El Fuqhari, about three miles south-east of Khan Yunis, on 6 July 1917). Then, on 19 July, Bailey’s Regiment set off south-eastwards on an excruciatingly tedious and uneventful three-day patrol, mainly at night because of the heat. The circular journey initially took the Regiment south-eastwards, i.e. in the general direction of Beersheba, a good 30 miles away, to the oasis village of El Melek (19 July), then westwards to the oasis village at El Gamli, near the Wadi Shanag (20 July), and then the long haul back to El Fukhari (21 July) – a total distance of no more than 20–25 miles. But on his return from the patrol, and without being too explicit about his Regiment’s locations and activities, he penned his exasperated impressions of his recent strenuous venture for the benefit of his family:

There are only 2 things that matter, water and shade. Those are first and second, and the rest nowhere, in this country, except yes, the third is air, the breeze that our tongues hang out for about 9 in the morning, when for sheer something to do I was reduced to cleaning my buttons this morning […]. There isn’t much else to be cheerful on when we are for ever thwarted of seeing the enemy, and condemned to wander at a weary walk, with constant mysterious stoppages at night, like a long goods train jolting and stopping and jolting on – On these occasions, when we halt, perhaps for 2 minutes, perhaps for an hour, I strap the reins to my wrist and lie down in the dust and sleep divinely – Most of my very naughty boys think they can sleep and hold the reins in their hands, and that usually means a stray horse in the dark, and my august remonstrance. Really, after the war, it oughtn’t to be possible to ever get bored.

The Regiment stayed at El Fukhari for another month, during which, from about 28 July until 18 August, Bailey attended a three-week-long topography course in Cairo. Just before leaving for Cairo, where he stayed at the Turf Club, he wrote an introspective and somewhat dispirited letter to his family in which he considered the possibility of having a good time while he was away, but concluded: “I shall never be young enough to have a jolly after 2 magnums of 54. Alas I never was. I have grown up halt & maimed in several of the most important things in life.” During his stay in Cairo, he received a copy of Kingham Old and New: Studies in a Rural Parish (1913), by William Warde Fowler (1847–1921), the Classics Tutor at Lincoln College, Oxford, who is best remembered for his studies of ancient Roman religion and festivals. Kingham was a classically picturesque Cotswolds village, about four miles south of Chipping Norton, whose history goes back well before the Norman Conquest. Having read Warde Fowler’s antiquarian account with some avidity, Bailey wrote to his family on 4 August 1917: “It would be hard to find any other book that brings back so many of the happiest things I have ever known – It makes one waver again between Scotland and the Cotswolds – Shall we ever be content with either of them by itself?” Bailey’s nostalgia for the stable continuities of Rupert Brooke’s timeless rural England, verging on acute home-sickness, is unmistakeable. On 18 August 1917, Bailey’s Regiment left El Fukhari and marched to El Sha’uth, a former Turkish stronghold three miles south-west of Tel el Fara, and on the same day, while returning by train to his Regiment from Cairo, Bailey described his three weeks in Cairo as “the 3 weeks of my military life, the 3 weeks because there was no soldiering about them”.

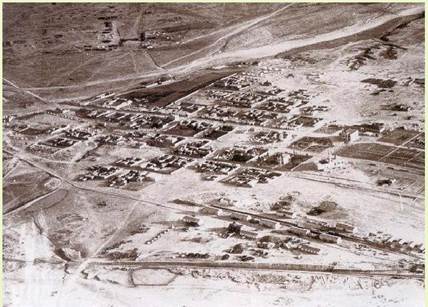

Beersheba (facing roughly eastwards) from the air (1917), with the railway, which went round the western side of the town and then curved northwards, visible at the bottom of the photo

1 September 1917 found Bailey’s Regiment in the desert area between Al Khasala, a town about ten miles south-west of Beersheba, and Asluj, a village with a railway station around twelve miles due south of Beersheba and seven miles south-east of Al Khasala, where Allied engineers were locating and repairing good ancient water wells in preparation for the coming assault on Beersheba, an important road and rail junction and a major source of water, that would form the first part of the Third Battle of Gaza (31 October–7 November 1917). During this period, Bailey was detached to report on Wadi Ausegi and the wells there; and the War Diary of Bailey’s Regiment records that at 17.00 hours on 12 September 60 enemy infantry had advanced from the Beersheba defences and attacked no. 2 post, which included a troop commanded by Bailey, but had withdrawn an hour later. On 18 September, Bailey’s Regiment, like the rest of the 22nd Mounted Brigade, returned to the “sea-side” at Tel el Maraqeb, where it rested and trained until 28 October 1917, when it marched back the 12 miles to El Shellal, where most of the Yeomanry Mounted Division, including Bailey’s 22nd Mounted Brigade plus a Brigade from the 10th (Infantry) Division, were already in General Headquarters Reserve. During this period, the rest of the 10th Division plus the other three infantry Divisions of XX Corps, the 60th, the 74th, and the 53rd, dug in around Beersheba from the west and south-west, and at 18.00 hours on the evening of 30 October 1917, units of the ANZAC Mounted Division and the Australian Mounted Division advanced towards Beersheba from the villages of Asluj (to the south) and Khasala (to the south-west). But the Turkish resistance was stronger than had been anticipated and on 31 October a stalemate was in danger of developing until, at 16.30 hours on 31 October 1917, Brigadier William Grant (1870–1939), with the 5th and 7th Australian Light Horse Brigades in support, led the 4th and 12th Australian Light Horse Brigades in a surprise attack on the town from the east which happened with such lightning speed that by 18.00 hours, the Turkish garrison, which lost roughly half of its number killed or wounded, had been overwhelmed and had either surrendered or withdrawn northwards. Although the Turks had had just enough time to destroy much of their pumping equipment, 15 out of the 17 wells were still intact and captured by the Australians who, quite apart from anything else, had shown the continuing effectiveness of cavalry in the right conditions.

Unlike the first two Battles of Gaza, the ensuing Battle of Gaza had three parts, the first of which is also known as the Battle of Tel el Khuweilfeh (1–6 November 1917), a small town in the southern Judean Hills, c.13 miles north-east of Beersheba, which also commanded significant water supplies. The second, but most important, part involved the well-prepared Turkish defensive line that curved downwards and westwards from Tel el Khuweilfeh, then went westwards through the village of Tel esh Sheria, where there were important wells and where the north–south railway line crosses the Wadi el Sheria, then through nearby Abu Hureira on the maritime plain and finally north-westwards to Gaza on the coast. And the third part involved a carefully phased attack on the city of Gaza itself which was, in the first place, designed as a diversionary operation until the outcome of the attack on Beersheba had become clear. But after the Australian success at Beersheba on 31 October, the attack on Gaza became more important in its own right. So after two-and-a-half weeks of bombardment (starting on 27 October 1917) by 68 pieces of heavy artillery supplemented by the armament of one cruiser and four monitors off-shore, and (starting on 1 November 1917), a week of fierce and unexpectedly prolonged fighting between the three Divisions of the Allied XXI Corps and the three Divisions of the Ottoman XXII Corps, the Turkish garrison, commanded by the extremely competent Mirliva (Major-General) Refet Bey (1877–1963), had withdrawn in good order from the city’s gutted and deserted ruins by midnight on 6/7 November, destroying roads, bridges and water-lifting plant as they went northwards. So when the Allies attacked Outpost Hill and Middlesex Hill, just outside Gaza, at 23.30 hours on 6 November and occupied them in the small hours of 7 November, they encountered no opposition.

Gaza after surrender to the Allied forces (1917/18)

On 3 November it was decided that the Desert Mounted Corps, which included Bailey’s Yeomanry Mounted Division, should prepare to attack the Turkish line on the following day, but water shortage problems caused the attack to be pushed back by two days pending the arrival of adequate supplies. By 4 November 1917, Bailey’s 22nd Mounted Brigade had reached Bir el Girheir, where it formed part of a thinly stretched outpost line near the Buqqar Ridge, the scene of very fierce fighting with the Turks during the four last days of October. On 5 November, the Corps entered Beersheba, after which it, together with XX Corps (see Charlesworth), marched north-westwards for three days up the Gaza road to the Turkish defensive line which straddled the road that linked Gaza with Beersheba and joined Abu Hureira in the west with Tel esh Sheria to the east. And while, on the morning of 6 November, three of XX Corps’s four Divisions attacked the four-mile-long Turkish positions at Tel esh Sheria, the 53rd Division, supported by dismounted units of the Yeomanry Mounted Division, successfully attacked their positions at Tel el Khuweilfeh, and by the evening of 7 November, the entire Turkish line between Abu Hureira and Tel esh Sheria had been overrun. So over the next two days General Allenby was able to recall cavalry units 20 miles westwards towards the fighting east and north of Gaza, and on 8 November the Allies took the town of Huj, seven miles east of Gaza, plus a significant amount of men and materiel, in a costly cavalry charge by two Yeomanry Regiments, in which, however, Bailey’s 22nd Brigade was not involved.

Allenby was determined that the Allied advance northwards should continue with the utmost dispatch – partly to prevent the retreating Turks from consolidating their positions and counter-attacking, as was their wont, and partly because the heavy winter rains, which usually began in the middle of November and were accompanied by very cold weather, would have turned the rich soil of the coastal plains to mud, making them almost impassable for heavy vehicles and very difficult going for both infantry and cavalry. So, from around 8 November, elements of the Yeomanry Mounted Division, including Bailey’s 6th Mounted Brigade, moved (north-)westwards across the desert towards the coast and then turned northwards parallel to the coast via Huj and Tel el Nejile (on the railway leading north from Beersheba; 10 November), to the Wadi El Mejdel (about ten miles north of Gaza and three miles north of Ashkelon; 11 November), a distance of about 20 miles, before advancing still further northwards via Hamameh and Abli Herazem to Jisr Esdud (probably modern-day Ashdod; 12 November). By doing so, the Division helped to form part of the protective screen of cavalry on the left of Allenby’s advancing army.

At 13.00 hours on 12 November, four rapidly reorganized Ottoman Divisions launched their expected counter-attack – not against the left of the Allied line, which was by now facing eastwards and poised to advance on Jerusalem through the bleak Judean Hills, but against the scattered Brigades of the Australian Mounted Division that had been protecting the right of the Allies’ line since 10 November. By doing so, the Turks aimed to outflank the Australian Light Horse Brigades and attack General Allenby’s army before it could take the strategically important railway station at Wadi es Sara that was known as Junction Station. For it was here that the branch line eastwards through the Judean Hills to Jerusalem and Damascus connected with the main line southwards to Gaza and Beersheba, and its capture would both split the Turkish Army in two and cut off the Turkish forces in the Judean Hills from the main lines of communication along the Palestine coast. It also had much-needed and plentiful supplies of water and modern, steam-driven pumping equipment. At first, the Turkish counter-attack forced the Australians to pull back southwards from Tel el Safi in the north through Balin and Barquaya in the east, but the Allied withdrawal was carefully conducted at the cost of relatively few casualties and by 18.00 hours the Turkish attack had petered out before the village of Summeil, c.12 miles south of Junction Station in the foothills of the Judean Hills. So the Turkish General leading the counter-attack decided not to involve his 3rd Cavalry Division by sending it into the battle-zone from its Reserve position east of Summeil.

Junction Station, Palestine (late 1917 or early 1918)

(Donor British Official Photograph Q12711)

On 13 November, the day when Allenby’s advance towards Jerusalem began in earnest at 07.00 hours, not least in anticipation of the heavy rains which, fortunately for the Allies, did not begin until 19 November, Bailey’s Brigade was involved in the capture of the village of Yebattalionah (the modern Israeli town of Yavna) by the Yeomanry Mounted Division. But after taking the village of Beshshit, the 52nd Division’s progress eastwards was hindered by determined Turkish resistance, especially at the fortified villages of Qatar and El Mughar, about three miles south of Yebattalionah, seven miles east of Beshshit, and nine miles south-west of the town of Ramleh, with the north–south El Mughar Ridge to the east of El Mughar presenting another major obstacle. So at c.14.30 hours it was agreed that two Battalions from the 155th (Southern Scottish) Brigade in the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division should deal with the villages while two Regiments of the 6th Mounted Brigade, Yeatman’s 1/1st Dorset Yeomanry and the 1/1st Buckinghamshire Yeomanry, covered by light artillery units and six machine-guns and with the 1/1st Berkshire Yeomanry in Reserve, should assault the Ridge. The attack began at 15.00 hours as a two-pronged charge across 3,000 yards of open terrain, followed by an assault uphill in the teeth of Turkish fire. One of the War Diaries described the Action as a “complete success”, for the crest of the ridge was quickly taken and secured, nearly 1,400 Turks were taken prisoner, 14 machine-guns and two field guns were captured, and the Turks suffered several hundred casualties killed and wounded. But according to the Regimental War Diary, the whole Action had cost the 1/1st Dorset Yeomanry alone 55 officers and ORs killed and wounded and 80 horses wounded and missing, and the fierce and equally costly fighting for Qatar and El Mughar continued until c.17.00 hours.

Meanwhile, as part of the general advance, Bailey’s 22nd Mounted Brigade was tasked with capturing the village of Akr (Aqir), some two miles north-west of Yebattalionah and a couple of miles east of the village of El Mughar and the newly captured Ridge. Bailey’s 1/1st East Riding Yeomanry led, with the 1/1st Lincolnshire Yeomanry echeloned on the left and the 6th Infantry Brigade on the right, with the 1/1st Staffordshire Yeomanry in Reserve. Although the British managed to take the high ground one mile west of Akr at 16.15 hours with relative ease, capturing two machine-guns and 71 prisoners in the process, the Turks, who were retreating eastwards in large numbers, resisted more strongly than had been anticipated, forcing the attackers to spend the night of 13/14 November outside the village. On the morning of 14 November 1917, the day that Junction Station was taken by some armoured cars and a Brigade of the 75th Division, Bailey’s Regiment occupied Akr at 06.30 hours, after it had been evacuated during the night, but lost 14 ORs killed, wounded and missing in doing so. Then, at 11.00 hours, the Regiment was ordered to descend from the hills and occupy the village of Ne`ane (also Naane, the modern-day town of Naan), roughly halfway (four-and-a-half miles) between the large town of Ramleh to the north and Junction Station to the south. Ne`ane’s importance lay in its railway station, a key strategic feature in the almost trackless Judean Hills, and Bailey, who was leading the advance guard (‘A’ and ‘B’ Squadrons), had explained their task to his men “in his methodical way”.